Imperialism and Revolution

Program #14

The conquest and peripheralization of Cuba

November 21, 2019

By Charles McKelvey

As we saw in our last episode, the conquest, colonization, and peripheralization of vast regions of the world by seven European nation-states from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries involved the imposition of systems of forced labor for the acquisition and export of raw materials, thus establishing a world-system. In the language of world-system analysts, such as Immanuel Wallerstein, the modern world-economy is characterized by a geographical division of labor, in which there is the core, the modern manufacturing center with diversity in production and high-wages; the periphery, which exports raw materials on a base of forced, low-wage labor and imports the surplus manufactured goods of the core; and the semi-periphery, which has a core-like relation with the periphery and a peripheral-like relation with the core. The structures of the world-system promote the development of the core and the underdevelopment of the periphery. Accordingly, global inequality is built into the economic structures of the world-system, the foundation of which was laid through conquest and colonialism.

We begin today with the particular case of Cuba. In this and subsequent episodes of our program on Imperialism and Revolution, we will discuss the conquest and peripheralization of Cuba, the Cuban revolution in opposition to colonial domination, the emergence of a neo-colonial Republic directed by the United States, the popular movement in opposition in neocolonial domination, culminating in the triumph of the Cuban Revolution; and the evolution of the revolution in power from 1959 to the present. In encountering the history and development of the Cuban Revolution, we will be looking for relevant insight with respect to today’s global structures of domination and the unfolding revolutions of the peoples of the world, which are seeking a more just, democratic, and sustainable world-system.

The peoples of Cuba prior to the Spanish conquest had migrated to the island from South America and from other Caribbean islands in different waves, the first occurring in 1000 B.C. and the last in the fifteenth century. Archeological evidence indicates that some lived in foraging bands of hunters and fisherman. However, at the time of the conquest, 90% of the indigenous peoples were food cultivators. They lived in villages of 1000-2000 people, constructing 20 to 50 multifamily houses. They developed a cooperative form of food production, and they cultivated a variety of crops. They also developed craft manufacturing.

As for the Spanish conquest of Cuba, words like holocaust and genocide are not too extreme. The indigenous population declined from 112,000 on the eve of the conquest to 3,000 by the 1550s.

The Spanish military conquest of Cuba began in 1511. The indigenous chief Hatuey, who had fled to Cuba with 400 followers during the Spanish conquest of the island of Hispaniola, organized a military resistance. Finding that their weapons were no match for the Spanish swords, shields, and horses, Hatuey and his followers undertook a strategy of guerilla resistance and were able to stop the Spanish advance for three months. But the Spanish eventually were able to capture Hatuey, and they executed him on February 2, 1512. The Spanish were able to attain effective control of the island by 1512.

In the aftermath of the Spanish military conquest of Cuba, gold nuggets were washed from riverbed sand, using the forced labor of the conquered. Father Bartolomé de las Casas documented the brutal treatment of the indigenous slaves, who toiled in the riverbeds from dawn to dusk. The exploitation of the gold ended in 1542, with the exhaustion of the gold and the near total extermination of the indigenous population, many of whom died as a result of the harsh conditions of forced labor. Many also died as a result of the disruption of their traditional agricultural system, which was displaced by a European system or was disrupted by the Spanish introduction of livestock that roamed freely, consuming crops and domestic animals. Also contributing significantly to the depopulation of the island was the spread of diseases against which the indigenous populations in America had evolved less immunity than Europeans, as a result of the indigenous relative isolation from the human migrations of Africa, Asia, and Europe.

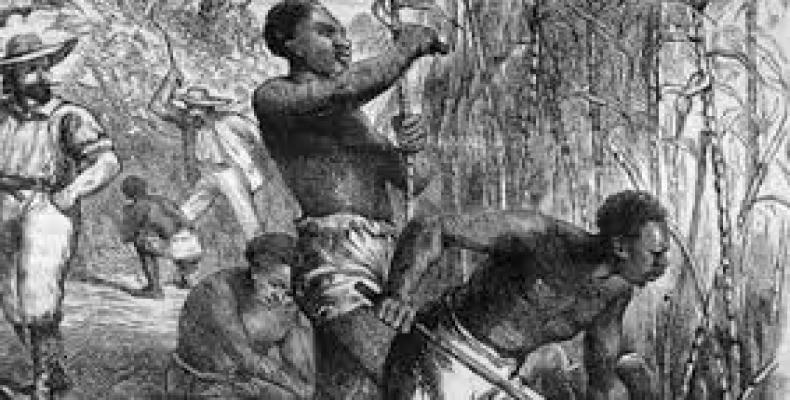

The obtaining of gold for export to Spain on a base of indigenous forced labor was the beginning in Cuba of the process of peripheralization, which involves the exportation of raw materials on a base of forced labor. From the sixteenth through nineteenth, Spanish colonial domination developed four system of forced labor, including, in addition to forced indigenous labor, African slave labor as well as the Spanish colonial labor systems of the encomienda and the repartimiento. There were five raw materials exported on the base of these systems of forced labor, including, in addition to gold, sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cattle products.

Cattle products, exported to Spain, or to other European nations via contraband trade, constituted the principal economic activity in Cuba in the period 1550 to 1700. The cattle haciendas, using low-waged indigenous labor legally sanctioned by the encomienda and repartimiento, were ideal for the conditions of limited supplies of indigenous labor and limited capital supply that existed in Cuba during the period.

Sugar plantations, oriented to export to Europe, were developed utilizing African slaves. They were first developed in Cuba at the end of the sixteenth century, and they continued to expand, especially after 1750, in conjunction with the expansion of the capitalist world-economy. Sugar plantations and slavery dominated the economy and defined the Cuban political-economic system during the eighteenth and most of the nineteenth century.

Coffee production, like sugar, was developed using African slave labor. It was never developed on the scale of sugar, but it was a significant part of the export economy of colonial Cuba. It expanded after 1750, and it received a boost in Cuba as a result of the arrival of slaveholders and their slaves from Haiti following the Haitian revolution

Tobacco production for export emerged in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Whereas sugar, coffee, gold, and cattle products were developed in Cuba in accordance with a peripheral function in the world-economy, tobacco production in Cuba was developed as a combination of peripheral-like and core-like characteristics. It was peripheral-like in that it was a raw material produced for export to the core of the world-economy. However, it was produced not by forced low-waged laborers but by middle-class farmers. By the first half of the eighteenth century, some tobacco growers had accumulated sufficient capital to develop tobacco manufacturing.

Tobacco production and tobacco manufacturing represented a potential for the development of Cuba that was different from the peripheral role represented by sugar, coffee, and slavery. During the first half of the eighteenth century, there was a possibility that Cuba would emerge as a semiperipheral nation, with a degree of manufacturing and economic and commercial diversity. Contributing to this possibility was the diversity of economic activities in the city of Havana, as a consequence of its role as a major international port. But with the expansion of sugar production after 1750, the peripheral role defined by sugar and coffee became predominant, although tobacco production by middle-class farmers and tobacco manufacturing continued to exist.

Consistent with the general patterns of the world-system, the peripheralization of Cuba created its underdevelopment. There were high levels of poverty and low levels of manufacturing. The vast majority of the people lacked access to education, adequate nutrition and housing, and health care. Relatively privileged sectors, such as tobacco farmers, tobacco manufacturers, and the urban middle class, found their interests constrained by the peripheral role and by the structures of Spanish colonialism. Only owners of sugar and coffee plantations benefitted from the peripheralization of the island, and even they were constrained by Spanish colonialism. Spain played a parasitic role, imposing taxes and a monopoly on commerce (via compulsory government trading posts), and lacking the capacity to provide markets for Cuban products or capital for investment.

These conditions gave rise to an independence movement in Cuba, initially formed during the nineteenth century by intellectuals of Spanish descent who forged consciousness of Cuban nationality. The ultimate achievement of the revolution of its aspirations would require it to create the unity of persons of European and African descent in defense of a project that envisioned not only political independence but also social and economic transformation of the structures imposed by Spanish colonialism. We will begin discussion of this Cuban quest for sovereignty in our next episode.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.