Imperialism and Revolution

Episode #28

The republic of Martí lives

February 27, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

In a previous episode of Imperialism and Revolution, reflecting on the 1902 Cuban Constitution, developed during the U.S. military occupation and following the dismantling of Cuban revolutionary institutions, we quoted Jesus Arboleya, who described the Constitution as “the burial of the Republic of Martí.” But just as revolutionary leaders live eternally; as their example, teachings, and spirit of struggle continue to be alive and present in the hearts and minds of the people; so it was that the republic envisioned by Martí continued to be alive. The soul of the nation, writes Cuban poet, critic, and essayist Cintio Vitier, was alive in the quiet suffering of the poor or middle-class family, in its capacity for resistance and hope, in its irrepressible popular laugh, in its unbeatable music, in the lamp of the intellectual, in poetry.” The nation that Martí had envisioned lived, hidden in the quiet sufferings and hopes of the people.

Intellectuals played an important role. Many sought “to discover and show the true face of the nation” in different ways, but united in “the common faith in education and culture as the road to national salvation.” Some, for example, sought to discover and exalt the ethical values that formed the foundation of Cuban nationality in the nineteenth century. In this vein, the anthropologist Fernando Ortiz described the saving virtues of Cuban culture, with particular emphasis on the immense contribution of the population with African roots, thus pointing to a de-colonization of Cuban culture. Others analyzed work of José Martí, focusing on particular aspects his complex thought, including the ethical, political-social, literary, journalistic, philosophical, and educational dimensions. Juan Marinello, for example, made a presentation at a meeting of writers and scientists in the Soviet Union, demonstrating the anti-imperialist character of Martí’s political thought and its opposition to the Cuban neocolonial regime. Marinello and others also placed the work of Martí in the context of Latin American thought.

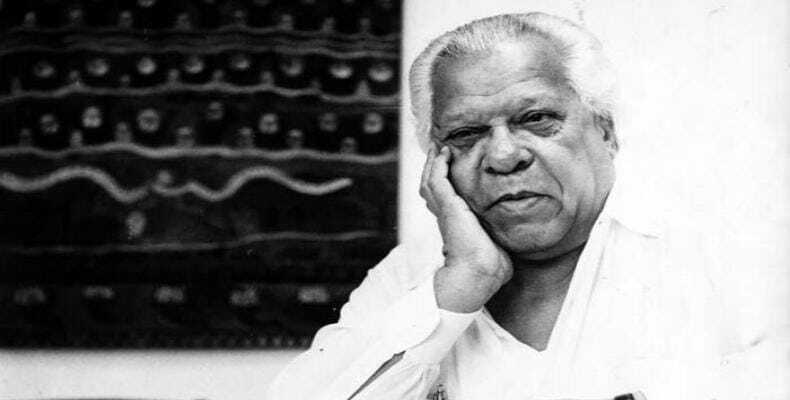

Cuban poetry also expressed a political and hopeful message in the context of the frustrations of the neocolonial republic. Nicolás Guillén, a member of the Communist Party of Cuba since 1937, was a poet whose work gave voice to the people, the concrete, exploited, and suffering people of the frustrated republic. He and other communist intellectuals believed that literary and artistic expression was a form of struggling for liberty and justice. In addition, Cuban poetry of the period affirmed the possibility of the impossible. Rejecting an interpretation of the impossible as meaning “not possible,” it sustained that the impossible possesses a light that most people cannot see, and a force that the prevailing attitude does not know. But the hidden light of the impossible can be made visible, and its unknown force felt. Accordingly, human hopes can experience incarnation. In the depths of the national soul is found a thirst for the historical awakening, for the incarnation of poetry in reality.

There also is in Cuban political culture a belief in heroism, which is rooted in the teachings of Martí, and which continues to be a central to the Cuban revolutionary project today. This dimension of the Cuban political culture is very different from the United States, where the Left has pointed out that the heroes of the American nation were defenders of their own class interests and, besides, were racist and sexist; where, in other words, the Left had taken heroes away from the people. In Cuba, there is a pervasive belief that there are heroes, a shared belief that emerged from the teachings of Martí.

In La Edad de Oro, a collection of stories written for children, José Martí wrote, “liberty is the right of all men to be honest, and to think and speak without hypocrisy.” Any person who obeys a bad government or unjust laws is not an honest person. Many people, he wrote, are living without dignity. They do not think about what is happening in their surroundings; they are content to live without asking if they are living honestly. Some persons, however, are not content to live without honesty and dignity. “When there are many men without dignity, there are always others that have in themselves the dignity of many men. They are the ones that rebel with terrible force against those that rob the peoples of their liberty and that rob men of their dignity. In these men walk a thousand men and an entire people; in these men, human dignity is expressed. These men are sacred.” Martí identified three such “heroes,” all of whom were leaders in the independence movements of Latin America in the early decades of the nineteenth century: Bolívar of Venezuela, San Martín of Río de la Plata, and Hidalgo of Mexico. Martí describes them as men who fought for the right of America to be free, and who protested the enslavement of blacks and the mistreatment of the indigenous peoples. They read the philosophers of the eighteenth century, observes Martí, and they explained the right of all to be honest and to think and to speak without hypocrisy.

Cintio Vitier maintains that Martí considered truth to be the highest duty of the human being. Accordingly, he believed that there can be no political liberty without spiritual liberty, and that “the first task of humanity is to reconquer itself,” that is, to know the essence of human life. He believed that through truth, honesty, and integrity, the impossible can be attained. Furthermore, Martí believed that the world is divided between “those who love and found, and those who hate and destroy.” In this conflict between good and evil, our duty is to stand on the side of the good, through the constant practice of generosity, service, and sacrifice; and through the cultivation of knowledge and the prudent exercise of reason. And reason must be accompanied by heart, by universal love, which brings us to identify with the weak and the oppressed and to cast our fate with the poor of the earth. Together, reason and heart provide human redemption.

Martí profoundly influenced the development of the Cuban revolutionary movement, establishing a fundamental moral perspective. Julio Antonio Mella, who founded the Communist Party of Cuba in 1925, embraced the notion of the need to sacrifice in defense of the great ideals. “All of the great ideas,” Mella wrote, “have their Nazareth.” This central concept of heroic sacrifice in defense of the moral world was kept alive by the intellectual class during the period of cynicism and fatalism of 1934-53. As a result of their efforts, the idea of heroic sacrifice would be central to the generation of young men and women who emerged as decisive political actors in the aftermath of the March 10, 1952, Batista coup, youth who possessed a sense of justice and believed that the world promised by the heroes and martyrs was in their hands to attain.

We will look in out next episode at the decisive political action of that exceptional generation of Cubans, who in the year of 100th anniversary of his birth, declared themselves, in both word and courageous deed, to be apostles of Martí, convinced that he remained alive in the hopes and aspirations of the people.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Sources

Arboleya, Jesús. 2008. La Revolución del Otro Mundo: Un análisis histórico de la Revolución Cubana. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Martí, José. 2006. La Edad de Oro, Sexta edición. La Habana: Editorial Gente Nueve.

Vitier, Cintio. 2006. Ese Sol del Mundo Moral. La Habana: Editorial Félix Varela.