Imperialism and Revolution

Episode #32

Revolutionary faith

March 26, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

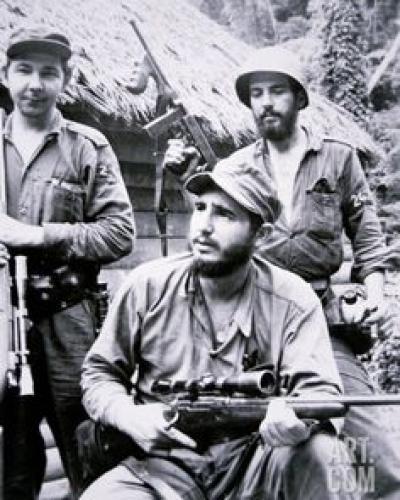

On December 2, 1956, Fidel Castro and 82 armed revolutionaries disembarked from the yacht Granma in a remote area of Eastern Cuba to launch a guerrilla struggle against the Batista dictatorship. The disembarking was a total disaster. The boat arrived two days behind schedule, thus undermining the strategy of a simultaneous uprising in Santiago de Cuba, intended to distract Batista’s army. As the rebels disembarked, they encountered swampland so difficult that they had to abandon most of their weapons. Three days later, they were surprised and routed by Batista’s army, dispersing in small groups and in different directions.

Fidel would not be deterred. When twelve of them were able to regroup under the protection of a local peasant, Fidel was jubilant. “We will win the war,” he declared. “Let us begin the struggle!” As described by Universo Sanchez, one of the twelve, it was “faith that moves mountains.” The faith of Fidel was not, observed Cintio Vitier, “a religious faith in supernatural powers, but a revolutionary faith in the potentialities of the human being.” It is an “uncontainable force” that “sees in history what is not yet visible.” Such faith proceeds from and is nurtured by three sources [writes Vitier]: “a moral conviction that defends the cause of justice; profound confidence in the human being; and the highest examples in human history.” And such faith is integrally tied to a dynamic view of human history: “for the revolutionary, [Vitier writes] it is not a matter of history been but of history being, where the highest examples continue acting; nor of a stagnant and fixed human being but of the human being becoming, in evolution.” And this becoming is above all “oriented toward duty.”

In the societies of the North, there is a pervasive lack of such revolutionary faith. Because of this, when there is commitment to social justice, it tends to be less-than-full commitment, abandoned when difficulties are encountered and sacrifice is required. It tends not to be a deep commitment, where a person is prepared to pay any price. The tendency toward less-than-full commitment to social justice in the North perhaps is rooted in the fact that the people of the North materially benefit from unjust global structures, and for them the attainment of social justice is not a life or death matter. Their commitment is rationalized away in threatening situations and in moments when sacrifice and hardship are required.

In addition, revolutionary faith is sustained by a historical perspective, and the cultures of the North tend to be ahistorical. Faith requires possessing a constant awareness of the long historical movement, seeing the present as a historic moment, which has been evolving from a long past, and is projecting itself into a foreseeable future. Revolutionary faith is anchored in discerning that future unfolding. But it is not an idealist vision of the future; it sees the future unfolding from actual and observable dynamics in the present, themselves unfolding from the observable past.

Possessing revolutionary faith is essential to the objective creation of that future reality that faith discerns. Vitier wrote that the unshakable faith of Fidel, “contagious, irradiating and attracting with the moral magnetism of heroism, . . . became a live experience in the terrain of the struggle.” Revolutionary faith, seeing the possibility of changing the objective conditions and the correlation of forces, itself is fed by the evolving social dynamics in which it was acting. In the case of Cuba, the guerilla forces in the mountains and the clandestine struggle in the cities were creating new objective conditions, in which the emancipatory possibilities for the future were becoming increasingly evident.

Vitier believed that the revolutionary faith of Fidel saved the revolution from falling once again into the abyss of the impossible, in which its fulfillment does not seem possible. But the faith of Fidel was not idealist. It was “nurtured by analysis,” which could discern the reality hidden by the perception of the impossibility of things, and it could discern that what appeared to be impossible was, in reality, possible and attainable.

The Northern tendency toward faithlessness is evident in the U.S. Left, when it indulges in criticisms of the socialist projects of Cuba, China, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. It sometimes criticizes the socialist projects from a liberal democratic point of view, seeing in them authoritarianism and ethnic discrimination. Often it criticizes them for not being socialist enough, on the basis of concept of a socialist theory that has been formed in the West and on a basis of limited socialist practice, thus violating the fundamental tenets that socialist theory is rooted in practice and must be adapted to the particular conditions. Accordingly, the U.S. Left criticizes the socialist nations for giving space to private property and for having inequalities. Such idealist and ultra-Leftist critiques of socialist revolutions are in some ways more damaging than critiques of the Right, because the ultra-Left criticisms are made by persons who give the impression of knowing something about socialism, and thus their commentaries are received with some creditability among the peoples of the North.

Central to the limitations of the U.S. Left is that it has not undertaken a sustained personal encounter with the socialist revolutions of the Third World, and it therefore does not discern their alternative logic, nor does it see their gains, attained despite the persistent and aggressive imperialism of the North. It has not seen their forging of structures of people’s democracy, constituting the basis for a political consensus to use the state to direct a plan for economic and social development, establishing the foundation for concrete gains in health, education, political and historical consciousness, culture, and sport. Not that the Third World socialist projects have attained perfection, which is not a possibility for human societies. What they are doing is advancing toward a new stage in human history, which represents an important phenomenon in contemporary global reality, not seen by the societies of the North, including the Left.

To see this progress, one has to encounter the Third World socialist revolutions of China, Vietnam, Cuba, and Nicaragua, as well as that of Venezuela, now in conditions of war with imperialism; as well as other socialist revolutions that could not sustain themselves, revolutions that were led by Evo in Bolivia, Correa in Ecuador, Allende in Chile, Nyerere in Tanzania, Nasser in Egypt, and Toussaint in Haiti, among others. Personal encounter with such revolutionary movements enables appreciation of the significant gains of colonized peoples during the last 200 years, changing the structures that the colonial powers imposed. Not only have the once-colonized peoples achieved political independence and formal recognition of their sovereignty. They also have formulated critiques of the neocolonial world-system, and acting in cooperation with one another, they have formulated the principles and values that can guide humanity in the creation of an alternative world-system that is more just, democratic, and sustainable, including such principles as cooperation and mutually beneficial trade among nations.

If we were to encounter the Third World socialist revolutions, we would possess the long, historical, and global view that would provide the analytical basis for revolutionary faith, which could be the foundation for our capacity to educate our peoples, with politically intelligent platforms and manifestos that explain what socialism is, that delegitimate capitalism as an anti-human project, and that embrace anti-imperialism as the necessary road for the future of humanity.

In Cuba in 1953, the attack on the Moncada Barracks galvanized the Cuban popular movement, enabling leaders with revolutionary faith to forge revolutionary unity and take political control of the nation. Perhaps the global coronavirus emergency is our Moncada.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Sources

Vitier, Cintio. 2006. Ese Sol del Mundo Moral. La Habana: Editorial Félix Varela.