Imperialism and Revolution

Episode #35

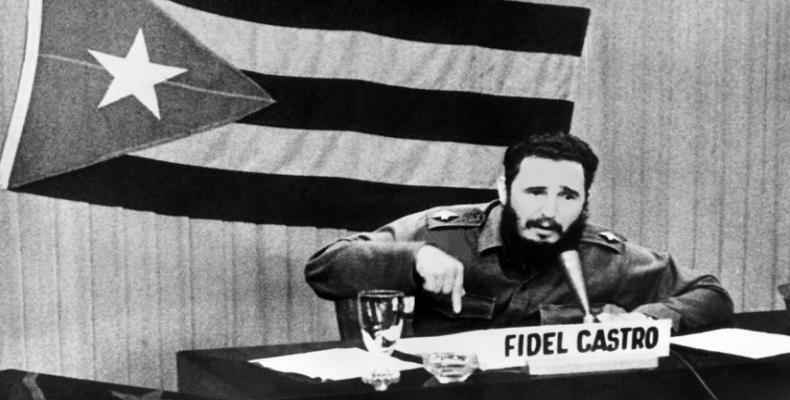

Fidel’s understanding of his personal leadership

April 16, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

At a meeting in the Sierra Maestra on May 3, 1958, the July 26 Movement named Manuel Urrutia as its candidate for president of the provisional government that would be formed upon the fall of Batista. Urrutia had not been part of the revolutionary movement, but he was appreciated for his vote as a judge in 1957, in which he affirmed, in opposition to the other judges in a trial against captured guerrillas and insurrectionists, the constitutional right of Cubans to resist oppression. On July 20 in Miami, representatives of the July 26 Movement established the Revolutionary Civic Front, a coalition of various parties and organizations that publicly affirmed their opposition to Batista and their support of his overthrow by means of armed struggle.

The Provisional Revolutionary Government that was formed following the triumph of the Revolution was a coalition of anti-Batista forces. Urrutia took the oath of office as president on January 2, 1959 in Santiago de Cuba. In subsequent days, a Council of Ministers was formed by Urrutia in consultation with Fidel and other leaders of the July 26 Movement. Most were lawyers who had ties with the national bourgeoisie. Only four of its eighteen members were leaders of the July 26 Movement

The revolutionary leadership sought to unify all political forces that were prepared to support the revolutionary process, which implicitly meant commitment to two fundamental principles. First, power to the people; the establishment of a government that responds to the interests of the people and not the interests of the national bourgeoisie, the wealthy, or any other particular interests. Secondly, opposition to U.S. neocolonial domination, and the establishment of Cuban sovereignty over its economy and its natural resources. The Revolution hoped to include various political forces in support of the revolutionary project, including the national bourgeoisie, insofar as it could sever its dependency on U.S. capital and reconstitute itself as an independent national bourgeoisie allied with a revolutionary project of autonomous economic development.

The Revolutionary Government designated Fidel as Chief of the Armed Forces, which was fully consistent with the de facto military situation, and at the same time, it was consistent with the concept of a coalition government. However, the logic of this designation functioned to obscure Fidel’s aversion to accepting any political position, which appears to have been rooted in several factors. In the first place, Fidel did not want to act out a historic pattern, in which a leader conducts a revolution to triumph and then assumes a position of head of state, and in a very short time is unpopular with the people. He believed that the period following the triumph is the most complex, and that the revolution would not be served at that moment by his assuming a political position, but rather, by his fulfilling a leadership role that was not tied to any particular position. His discourses imply that he believed that leading a nation from neocolonial dependency to true sovereignty requires exceptional capacities of leadership, but on the other hand, the leadership capacities and moral commitment necessary for public office are not of an exceptional nature; and that there were many leaders in the July 26 Movement that possessed these necessary qualities for high public office. Moreover, he expressed personal dislike for many of the tasks that come with political office. There are many important details that must be attended, and although necessary, they are time consuming and not necessarily fulfilling. He wanted to be emancipated from such duties, and to be free to dedicate his time and energy to revolutionary work for which he was especially qualified, such as serving as head of a group to formulate an agrarian reform proposal; meeting with the people in various settings in order to appreciate their concerns; meeting with representative of various political parties and currents of thought in order to assess the possibilities for coalition; and representing the Revolution in international settings. He did all of these things in January, 1959, before he was persuaded to accept the position of Prime Minister.

He agreed on February 13 to accept the post of Prime Minister, having been requested to do so because of the dysfunctional character of the coalition government, even though he personally believed that the Revolutionary Government ought to be able to resolve its problems without his intervention. Subsequently, for the following five months, he effectively led the Council of Ministers in the enactment of a number of important revolutionary laws and measures.

However, problems came to the surface in July, in what Fidel described as a plot supported in the exterior in which President Urrutia and a Cuban military officer would denounce the Revolutionary Government for being communist. Fidel considered the conspiracy to be a betrayal of the revolution and the nation. He knew that he would have the support of the Council of Ministers and the people, if he were to denounce the President and replace him, either with himself or a political ally. But he did not want to damage the revolution by presenting an international image of its leader as a classic caudillo who removes and installs presidents. So, he decided to denounce the president for his counterrevolutionary conspiracies and to himself resign as Prime Minister, and to leave it to the Council of Ministers to decide what to do about the treacherous President and the now-vacant Prime Minister post.

Fidel resigned as Prime Minister on July 16 and appeared on national television on the evening of July 17 to denounce the conduct of the President and to explain that he does not want to be known throughout the world as a deposer of presidents, that he is not resigning from the Revolution but from a particular post that he never wanted, and that he wants to serve the Revolution in other ways. He explained to the people that he never envisioned his role following the triumph of the revolution as that of occupying a position in the government as head of state.

I first read Fidel’s July 17, 1959 televised remarks some sixty years after the fact, and I find that I see his point. The Revolution, rather than confining him to a position, could have used his exceptional capacities to respond to various challenges and to develop important long-term projects.

But sixty years ago, the people, including a portion of the revolutionary leadership, were not ready for Fidel’s concept of special revolutionary leadership for a person with exceptional capacities. The people refused to accept his resignation. They overwhelmingly declared that the President should resign, and they called on the Council of Ministers to not accept Fidel’s resignation. In the face of this public reaction, Urrutia immediately resigned, and the Council of Ministers named Osvaldo Dorticós as President. Fidel’s resignation had not been accepted by the Council, but Fidel persisted in his determination to not return and to move the Revolution to a more advanced understanding of leadership. The popular demand for Fidel’s return continued for days, including work stoppages and the suspension of the chiming of church bells. The popular call culminated in a mass act on July 26 in the José Martí Civic Plaza, in which one million peasants arrived to defend the Agrarian Reform Law and support the revolution. During the act, the speakers and the assembly repeatedly called for the return of Fidel to the government. Eventually, Dorticós took the microphone and proclaimed, “In the most emotional moment of my life, I am able to announce that today our comrade Fidel, before our mandate, has agreed to return to the office of prime minister.”

And so it was that the radical anti-neocolonial wing of the anti-Batista coalition consolidated its control of the revolutionary process, proceeding with ideological clarity to the reconstruction of the neocolonial order and the uncompromising defense of the sovereignty of the nation. But there was a cost, namely, a dependency on the exceptional leadership of one person. The revolution used that dependency to its advantage, as Fidel’s pedagogical speeches played a central role in the forming of the revolutionary consciousness of the people. In addition, Fidel did not abandon his vision of his life work. He involved himself in expansive ways in some projects, going far beyond the requirements of office, dedicating himself to an extraordinary revolutionary labor in Cuban leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement and in the development of Cuban scientific research centers. Meanwhile, the problem of authority concentrated in one person was acknowledged and addressed. Beginning in the 1960s, the revolution sought to form a vanguard political party which would function to institutionalize the moral and teaching authority of Fidel, replacing the moral and teaching authority of one person with that of a vanguard political party, the Communist Party of Cuba. The Party, however, does not have the legal authority to decide; such authority resides in the National Assembly of People’s Power, which is elected by the people and which designates the persons for the various government positions, such as President, Prime Minister, and the various minsters.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Sources

José Bell Lara, Jose, Tania Caram León & Delia Luisa López García. 2020. Fidel in the Cuban Socialist Revolution. Translated by Charles McKelvey. The Netherlands: Brill Publishers

Buch Rodríguez, Luis M. and Reinald Suárez Suárez. 2009. Gobierno Revolucionario Cubano: Primeros pasos. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.