Imperialism and Revolution / Episode #37

Rupture with the neocolonial hegemonic power

April 30, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

A principal task of the triumphant Cuban Revolution was, in the words of the Cuban intellectual Jesús Arboleya, “the breaking of the political and economic ties that established the dependency of the country in relation to the USA, and the end of the neocolonial model established at the origins of the republic”.

The key step that broke with the neocolonial order and established the anti-neocolonial character of the Revolution was the Agrarian Reform Law of May 17, 1959, which expropriated large sugar and rice plantations and cattle estates, providing for compensation in the form of twenty-year bonds, with prices determined by the assessed value of the land for tax purposes. More than four thousand plantations were expropriated, with approximately one-third of the acreage distributed to peasants and two-thirds becoming state property, utilized for the establishment of farms and cooperatives.

As Arboleya has written, “The Agrarian Reform Law . . . constituted a fundamental ingredient of the political program of the Cuban Revolution, inasmuch as agrarian property ownership constituted the economic means of support of the national oligarchy and the neocolonial system as a whole. Transforming this reality not only was a requirement in order to advance the social improvements demanded by the revolution, but it also meant a radical change in the reigning structure of power in the country. . . . The principle objective of the agrarian reform was the banning of plantations, with the intention of giving a death blow to the Cuban oligarchy and the large US companies. In this manner the agrarian reform defined the anti-neocolonial character of the revolution.”

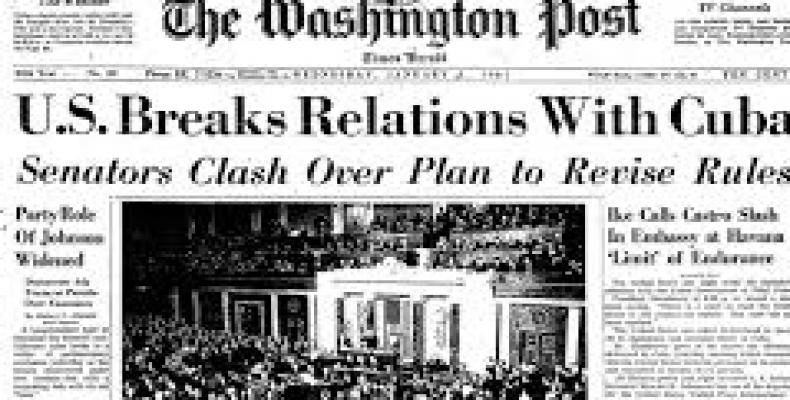

The U.S. government launched an ideological campaign against the Cuban Revolutionary Government, invoking the phantom of communism. On March 17, 1960, the Eisenhower Administrated initiated the planning of a U.S.-backed military invasion carried out by Cuban counterrevolutionaries based in Miami. On July 2, 1960, the U.S. Congress authorized the President to amend the U.S.-Cuba sugar quota; and on July 6, President Dwight Eisenhower reduced the U.S. sugar purchase to 23% below the quota, seeking to provoke economic difficulties in Cuba. Following the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion of April 17, 1961, the U.S. government turned to an embargo on trade with Cuba and to the support of terrorist activities on the island, supporting counterrevolutionary terrorist organizations based in Miami. The goal of U.S. policy was what we today call regime change, seeking to re-establish a government subordinate to U.S. interests, in accordance with the requirements of the neocolonial world order.

The Cuban Revolution did not want conflict with the United States; it wanted cooperation on a foundation of respect for its sovereignty. On July 6, 1960, the Revolutionary Government emitted a law that authorized the President and the Prime Minister of Cuba to nationalize U.S. properties by means of a Joint Resolution. The Law provided for compensation for the nationalized properties through thirty-year government bonds, financed through a fund that would be fed by Cuban government deposits in an amount equal to 25% of the value of the U.S. purchase of Cuban sugar in excess of the sugar quota. The Law, therefore, proposed a mutually beneficial resolution, linking compensation for nationalized properties to the U.S.-Cuban sugar trade. By means of a higher U.S. sugar purchase and Cuban use of the additional income to finance compensation and invest in industrial development, the law in effect proposed the transformation of core-peripheral exploitation into North-South cooperation.

The Cuban proposal, however, was rendered impractical by the simultaneous reduction of U.S. purchases below the sugar quota (announced on the same day, July 6), and by its subsequent policy of regime change. Nevertheless, thirty days later, during the announcement of the first nationalizations under the Law, Fidel appears to remain hopeful that the U.S. government will accept the proposal of compensation through U.S. purchase above the sugar quota.

The Revolutionary Government, under the authority of the July 6 law, emitted three joint resolutions that nationalized all U.S. properties in Cuba. The first, announced on August 6, 1960, nationalized twenty-six U.S. companies, including twenty-one sugar companies. The Resolution explained the historical context and the necessity of the expropriation of U.S. owned sugar lands, noting that “the Sugar Companies seized the best lands of our country” in the first decades of the twentieth century, during an invasion of “insatiable and unscrupulous” foreign capitalists, who “have recuperated many times the value of what they invested;” and noting that “it is the duty of the peoples of Latin America to be inclined toward the recuperation of its national riches, taking them away from the control of the monopolies and foreign interests that impede the progress of the peoples, promote political interference, and infringe upon the sovereignty of the underdeveloped peoples of America.” In accordance with the Agrarian Reform Law of 1959, the expropriated land was used to develop state-managed agricultural enterprises; or it was distributed to peasants, each receiving a “vital minimum” of 26.85 hectares.

Joint Resolution #1 also nationalized a U.S.-owned electricity company and a U.S.-owned telephone company, both of which charged notoriously high rates, the reduction of which had been a popular demand prior to the triumph of the revolution. In addition, the Joint Resolution nationalized three oil refineries, which historically had set a higher price for Cuban distributors; and which had refused to process Soviet crude that had been purchased at a favorable price by the Cuban government, compelling the government to invoke a 1938 agreement and order the refining of the oil. Under state ownership, electricity and telephone rates and gasoline prices were significantly reduced.

Joint Resolution #2 of September 17, 1960 nationalized the three U.S. banks in Cuba. Historically, the crediting policies of the U.S. banks had favored Cuban exportation of raw materials and importation of U.S. manufactured goods, thus restricting Cuban industrial development. Since the triumph of the Revolution, the banks had adopted policies designed to reduce U.S.-Cuban commerce, supporting the efforts of the U.S. government to suffocate the Cuban economy.

Joint Resolution #3, issued by the Revolutionary Government on October 24, 1960, authorized the nationalization of the remaining 166 U.S. properties in Cuba. They included 28 insurance companies, 18 chemical companies, 18 mining companies, 15 machine importing companies, 11 hotels and bars, and 7 metallurgical companies. These nationalizations were a response to the continuing aggressiveness of the U.S. government toward the Cuban Revolution, including its October 19 prohibition of the export of U.S. merchandise to Cuba.

Lacking support from the U.S. side for cooperation or negotiation with respect to compensation for the nationalized properties, revolutionary Cuba continued on its sovereign road, which included the proclamation of the socialist character of its revolution; and the development of popular democracy, with mass organizations, mass assemblies, neighborhood nomination assemblies, and assemblies of popular power, alternatives to the structures of representative democracy.

The United States, meanwhile, continued with its policy of regime change, maintaining a prohibition on economic, commercial, and financial transactions with Cuba. The Helms-Burton Law of 1996 codified the economic measures that had been directed against Cuba since the Kennedy administration. The Law allows for the ending of coercive economic measures when Cuba becomes democratic, in accordance with the U.S. concept of democracy. As a result of the failure of the blockade to effect regime change in Cuba, the Obama administration initiated the normalization of relations, adopting an alternative imperialist strategy of promoting change in Cuba through support of Cuban small proprietors. The Trump Administration, however, has reversed Obama and has intensified the blockade, including the full implementation of Helms-Burton.

The Cuba-USA conflict remains unresolved. The United States seeks to restore its declining hegemony, or to act multilaterally with other core powers, in the context of a neocolonial world-system; whereas Cuba exercises its sovereignty, at variance with the requirements of the neocolonial world order, but consistent with principals declared in the Charter of the United Nations.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Reference

Arboleya, Jesús. 2008. La Revolución del Otro Mundo: Un análisis histórico de la Revolución Cubana. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.