When we do not see the Third World, we do not understand the logic of China

By Charles McKelvey

May 22, 2020

When intellectuals, activists, and politicians of the North do not see the Third World, they do not see the logic of China. When I say “do not see,” I mean paying little attention. To what extent have intellectuals and activists of the North immersed themselves in the Third World revolutions, allowing new understandings to challenge their assumptions? Have they given attention to the conferences of Bandung and Belgrade, where leaders of the anti-colonial struggles met to affirm common principles, culminating in 1974 with the declaration of a New International Economic Order by the General Assembly of the United Nations? Are they aware that, since 2006, the 120 nations of the Non-Aligned Movement have retaken the principles of the Third World project of 1955 to 1982, to once again proclaim and demand an international order based in the principle of respect for the sovereignty of nations, thus standing against the neoliberal weakening of states?

When we do not see the Third World, it is easy to misinterpret China, because the Third World and China have been shaped in similar contexts, and they therefore have similar assumptions, concepts, and strategies. They possess a similar logic. For this reason, for the last sixty-five years, they have been for the most part allies.

For most of the last two millennia, China was one of the most advanced civilizations of the world. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the European presence in Southeast Asia was still limited, the Chinese economy was characterized by technological advances and economic growth. There was an expanding domestic trade in cotton, textile manufactured goods, ceramics, rice, tea, sugar, and handicraft products for farmers. A merchant class, market towns, and trade guilds were growing; banking and finance were developing. Although international trade was limited, it was a vibrant trade in the Southeast Asia region, consisting of the import of spices and the export of silk and tea, not connected to the limited European presence in the region. Technological advances in agriculture sustained population growth. And British cloths could not penetrate the Chinese market, due to the strength of Chinese textile manufacturing.

China, however, did not experience the modernization of its industry, as did Northwestern Europe from 1750 to 1850. In Chinese economic development, there was nothing comparable to the impact of the gold and silver from Spanish colonial America on Northwestern Europe in the sixteenth century, which stimulated the modernization of agriculture and the expansion of manufacturing; or the European colonial domination and peripheralization of vast regions the world from 1750 to 1914, which provided cheap raw materials and new markets for Northwestern European manufacturing, stimulating its modernization. Lacking a stimulus to overcome institutional and cultural constraints to modernization, the Chinese state became weaker during the nineteenth century, losing its capacity to carry out administrative functions like flood control and the storage and distribution of grain. Demoralization and corruption in government grow. Domestic rebellion and foreign invasion became major threats.

The British invasion by gunboat beginning in 1839 (launching the Opium War of 1839-42) led to the Treaty of Nanjing of 1842, which opened five “treaty ports” and gave the barren island of Hong Kong to the British. This was the beginning of what the Chinese called the “unequal treaties.” Subsequent treaties signed by China with Britain, the United States, France, and Russia established more than 80 treaty ports and facilitated greater penetration by Western commerce. The treaties set low tariffs that did not protect Chinese industry, leading to a partial de-industrialization. The treaty system operated from 1842 until 1943.

Unlike the Third World, China was not conquered, colonized and peripheralized, and therefore it was a never a great supplier of raw materials for the West. However, like the Third World, its traditional manufacturing capacity was weakened by imposed economic accords, and it was reduced to purchasing the manufactured goods of the West.

The Chinese Revolution led by Mao opposed the unequal treaties and the foreign imperialism that they represented, and it advocated the modernization of China and the restoration of its autonomy. Following the triumph of the Revolution, modernization was attained on the base of the liquidation of the landholding class, putting the land in the control of the peasants and the state, and placing the state under the direction of the delegates of peasants, intellectuals, and workers.

It is as logical for the People’s Republic to be allied with and to cooperate with the Third World project as it is for the Third World nations to be allied with each other. China and the nations of the Third World have the common experience of foreign penetration and a common interest in nullifying imperialism; and they have a common interest in South-South cooperation, creating economic relations that circumvent imperialist designs. If we do not see the Third World, we do not see China’s relation with the Third World, and we overlook its anti-imperialist logic.

If we are not paying attention to the Third World, we may not have seen the practical relation between the Third World and China, including some of its significant recent developments. We may not have noticed that the 33 governments of Latin America and the Caribbean established in 2010 CELAC, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, which declared at its Second Summit in Havana in 2014 its commitment to a form of integration based on solidarity and cooperation. We might not have taken note of that Summit’s approval of the creation of a China-CELAC Forum. We not be aware that in July of that year the heads of state of China and the countries of Latin American and the Caribbean met in Brasilia to establish the China-CELAC Forum.

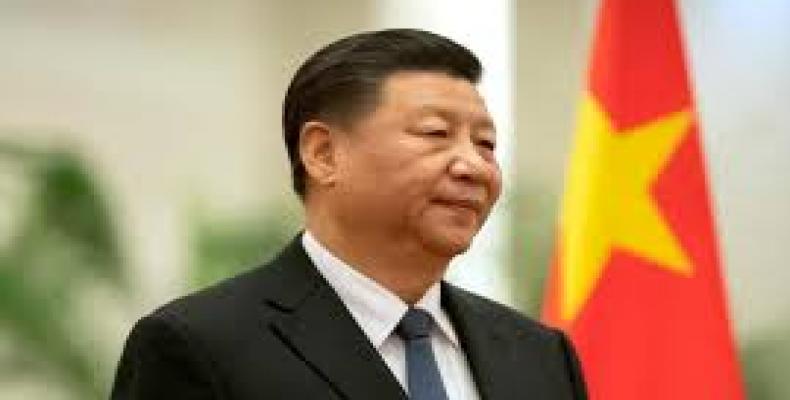

In an interview with Latin American journalists during his travel to the China-CELAC Forum, Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic, described China, with some accuracy, as a large nation, but not a global power, and in a phase of development similar to Latin America and the Caribbean nations. He maintained that China is seeking to develop through trade based on cooperation and win-win relations of mutual benefit. He defended South-South cooperation as the engine that can drive the autonomous and sustainable development of the underdeveloped nations, and he observed that the expanding economic and social relation between China and CELAC to be an example of this necessary South-South cooperation. He affirmed the commitment of China to an alternative international economic and political order, more just and reasonable.

If we do not see the Third World, we may not be aware that the leaders of the governments in the front line of the process of Latin American union and integration regularly praise the cooperative road that China is taking. The leaders of these nations, the historic victims of imperialism, know well what imperialism is. They know the difference between trade that is imperialist and trade that is cooperative, and they know how to denounce the former. They are not in the habit of giving false praise to imperialist powers.

They discern that China has a common interest with Third World nations in developing a new international economic order, that China’s interest is not in domination of the established neocolonial world-system, but in leading the colonized peoples toward the building of an alternative world-system that respects the sovereignty of nations. China has a fundamental economic and political interest in a world in which imperialism is abolished, and it recognizes its capacity to play a leading role in forging an alternative more just, democratic, and sustainable world-system.