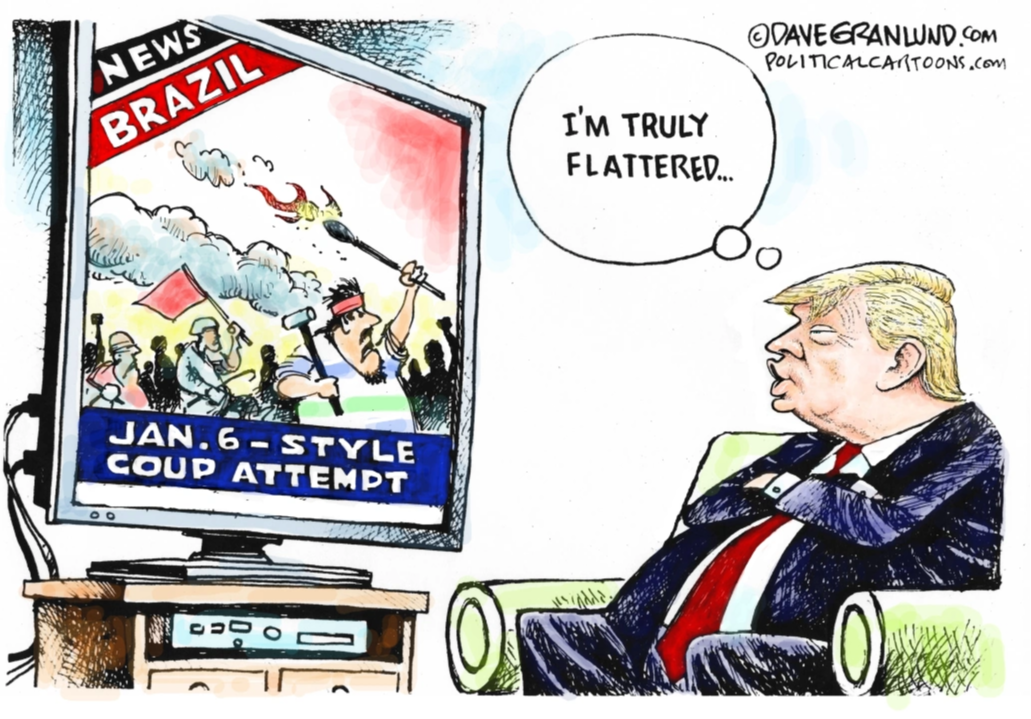

There are unmistakable parallels between the events of Jan 6, 2021 and Jan 8, 2023, as well as between the prime movers of the two violent mobs: Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro

Brasilia, May 30 (RHC)-- On January 8th, supporters of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro stormed and ransacked important government buildings in Brasilia, including the country’s Congress, the Presidential Palace and the Supreme Court. In scenes reminiscent of the January 6, 2021 insurrection in Washington DC, Bolsonarists demanded that the result of the presidential election of October 2022 be overturned.

The uprising, lasted a little more than three hours. President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva vowed to “punish” the wrongdoers and has blamed Bolsonaro, who had left on a flight to Florida and never officially conceded defeat, for inflaming his supporters with false rhetoric on election fraud.

Bolsanaro and Trump are among the rightwing populist leaders who have come to power in several countries by harnessing popular anti-establishment sentiment through intense anti-globalist and anti-minority rhetoric, and who have subsequently gone on to attack and subvert a range of democratic institutions in their countries.

Trump and Bolsonaro have openly expressed support and admiration for each other, and Trump has earlier urged Brazilians to vote for the “Trump of the Tropics,” as Bolsonaro is often called.

The events in Brazil on January 8th were a near-replay of what happened at the United States Capitol two years ago. In both cases, angry supporters of a president who had been defeated in an election — unfairly, they believed — stormed government buildings with the intention of “taking back” their country. In both cases, they were egged on by their leaders — Trump and Bolsonaro — with baseless claims of election fraud.

In a speech on December 2, 2020, Trump said, “If we don’t root out the fraud, the tremendous and horrible fraud that’s taken place in our 2020 election, we don’t have a country anymore.”

Two years later, Bolsonaro’s son used almost identical language, claiming that his father was the victim of “the greatest electoral fraud ever seen.”

Both claims were debunked by authorities and the media in the two countries. But the claims of the leaders and their repeated parroting by their diehard followers was “proof” enough for many. Social media was used to spread disinformation and to organise demonstrations and protests against the “stolen elections.”

The parallels between the uprisings in Washington DC and Brasilia are not coincidental. Rather, they are a part of a common playbook that rightwing populists have used to exploit anti-institutional anger and ultra-nationalist urges.

The rise of leaders like Trump and Bolsonaro – also Viktor Orban of Hungary, Marine Le Pen of France, Geert Wilders of the Netherlands – has been situated in the context of growing wealth inequalities and changing racial and gender dynamics that have put people’s lives and identities in flux and engendered widespread insecurities. Right wing populism is a direct outcome of this, and grows by channelling people’s fears and frustrations.

Philosopher and political scientist Noam Chomsky said in an interview that right wing populism is a manifestation of the “general collapse of the centrist political institutions during the neoliberal period.”

He said, “What is taking place is reminiscent of Gramsci’s observations about an earlier period, ‘when the old is dying and the new cannot be born’; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”