Imperialism and Revolution

Episode #26

The return of neocolonial “democracy”

February 13, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

In last week’s episode of Imperialism and Revolution, we saw that in the period 1934 to 1937, Fulgencio Batista established institutions that placed education and social services under the control of the Army; and his policy of subordination to U.S. interests deepened the unequal core-peripheral trade relation between the United States and Cuba. In today’s episode of Imperialism and Revolution, we look at the return to representative “democracy” in the context of the USA-Cuba neocolonial relation.

The evolving structures of the first Batista dictatorship of 1934 to 1937 constituted a turn toward fascism. Particularly important were the putting of political decisions in the hands of the military chiefs; the placing of education and social services under the direction of the military; the repression of the Communist Party and urban-based workers’ organizations and leaders; and populist rhetoric, propaganda, and social programs oriented to the rural population, conceived as the social base of the government. The system generated internal opposition from marginalized civilian politicians, who represented the interests of Cuban plantation owners and industrialists, and from professionals in education and other social services. Moreover, the urban-based popular movements were growing in strength, in spite of the repression and demagoguery of the regime.

In addition to generating internal opposition, such fascist structures were incompatible with the U.S. neocolonial objective of a form of domination that had the appearance of democracy. Moreover, Batista’s turn toward fascism was inconvenient with respect to international developments of the time. In 1933, fascism had triumphed in Germany, which rapidly began to militarize and to pursue an expansionist foreign policy. Beginning in 1935, communist parties formed anti-fascist “popular fronts” with bourgeois-controlled political parties. As global contradictions intensified heading into World War II, the Western representative democracies and the Soviet Union moved toward alliance.

Batista’s political power was based on his relations with U.S. ambassadors. From 1934 to 1937, Batista and Ambassador Jefferson Caffery maintained close personal ties, and certainly Caffery gave his approval to the direction that Batista was taking. But Caffery was replaced by a new ambassador, J. Butler Wright, on August 17, 1937. Distinct from Caffery, Wright attended to the interests of other Cuban sectors, not only Batista, that are important in sustaining the neocolonial relation. He tutored Batista toward an approach more compatible with the U.S. concept of neocolonial domination with a democratic face, and more consistent with recently emerging global tendencies and alliances.

In December 1937, Batista emitted a decree of amnesty for 3,000 political prisoners, and in 1938, Batista made reforms that resulted in greater protection of civil and political rights. During that same year, Batista also announced the convoking of a constitutional assembly, a long-standing demand of the popular movements. In addition, Batista negotiated with Ramón Grau, head of the Authentic Cuban Revolutionary Party, the participation of the Authentics in the elections, ending the persistent policy of the Authentic Party of abstaining from elections. In addition, on September 13, 1938, the Communist Party of Cuba and other organizations were legalized, so that the PCC could now conduct its work of organization and popular education openly and without fear of repression.

Elections for the Constitutional Assembly were held on November 15, 1939. Eleven political parties nominated candidates for delegates to the Assembly. The parties were organized in two coalitions, one headed by Batista, and an opposition coalition headed by Grau and the Authentic Revolutionary Party. The Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) had proposed the incorporation of its candidates into the coalition headed by Grau, in accordance with the 1935 guidelines of the Communist International that its affiliated parties form anti-fascist popular fronts with bourgeois-controlled political parties, in order to prevent victory by the fascist Right. However, the PCC proposal for its incorporation was rejected by the Authentic Party, reflecting a continuing anti-communism.

At the same time, Batista was moving away of fascism, and the bourgeois parties of the Batista coalition offered to include important aspects of the PCC program into the Batista bloc platform. The Communist Party, therefore, decided to enter the coalition headed by Batista.

The Cuban scholar Jesús Arboleya maintains that the alliance with Batista was politically costly for the PCC, and that many Cuban historians consider it to have been a “strategic error,” that is, an error from which the PCC never recovered.

As a result of these political dynamics, the elections for delegates to the Constitutional Assembly offered to voters a confusing scenario. There was, on the one hand, the opposition bloc headed by the well-known reformer but anti-communist Grau; and on the other hand, the bloc headed by the dictator Batista, who had been cultivating a democratic image and who now was allied with the Communist Party. Seventy-six delegates were elected, forty-one belonging to the four parties of the opposition bloc, and thirty-five pertained to five parties of the Batista bloc, including the Communist Party.

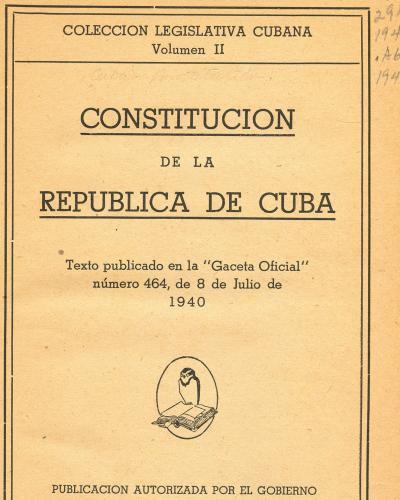

The Constitutional Convention was convened on February 9, 1940. Delegates of nine parties participated in the debates, and all delegates were free to express personal views. Juan Marinello, Blas Roca, and Salvador García Aguero, three of the six delegates of the Communist Party, provided important defenses of the rights of workers, peasants, and other popular sectors. The new Constitution was approved by the Constitutional Convention on June 8, 1940, followed by a ceremonial signing on July 1, 1940. The Constitution of 1940 was a product of the advances in theory and in practice of the Cuban popular movement, and it was advanced for its time. It recognized the full equality of all, regardless of race, color, sex, class, or similar social condition, and it affirmed the rights of women to vote and hold public office. It included articles on the regulation of work, including the obligation of the Cuban state to provide employment, the establishment of a maximum workday of eight hours and a maximum workweek of forty-four hours, and the recognition of the right of workers to form unions. It recognized the principle of state intervention in the economy, and it declared natural resources to be state property. It abolished large-scale landholdings, and it established restrictions on the possession of land by foreigners. It established protections for small rural landholders, and it obligated taxes on sugar companies.

With respect to the restrictions on foreign ownership of land, the US government and its Cuban allies had attempted to limit the scope of the Constitutional Convention, concerned that it could establish restrictions on foreign ownership. But these interventionist maneuvers were denounced and repudiated by the popular sectors.

General elections were convoked for 1940. Batista and Brau were the presidential candidates. Having the support of the alliance of the bourgeois parties and the Communist Party, Batista attained a solid victory, with 800,000 votes, as against 300,000 for Grau, in a total population of four and one-quarter million. The election results were accepted by all as fair.

The return to neoliberal democracy occurred at a time in which economic conditions were favorable. World War II had disrupted sugar production in many countries, creating relatively high prices for Cuban sugar. At the same time, U.S. industry was reconverting to the manufacturing of arms and war materiel, disrupting the flow of manufactured goods to Cuba, thus creating possibilities for Cuban national industry.

Cuba had arrived to be a what Jesus Arboleya has called a “perfect neocolonial system,” with the channeling of popular movements in a reformist direction; with the appearance of democracy through elections; with a degree of economic space for national industry, without contradicting the interests of international capital; and with a level of political space for a political class centered around the military leadership, headed by Batista, which had a cooperative relation with the US government.

However, as will see in our next episode, the perfection would be short lived. The neocolonial republic would soon enter into crisis again.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Sources

Arboleya, Jesús. 2008. La Revolución del Otro Mundo: Un análisis histórico de la Revolución Cubana. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Chang Pon, Federico. 1998. “Reajustes para la estabilización del sistema neocolonial” in (IHC, 1998).

Instituto de Historia de Cuba (IHC). 1998. La neocolonia. La Habana: Editora Política.

López Segrera, Francisco. 1972. Cuba: Capitalismo Dependiente y Subdesarrollo (1510-1959). La Habana: Casa de las Américas.

Ramos, Juan Ignacio. 2010. “Introducción” in La Internacional Comunista: Tesis, manifiestos, y resoluciones de los cuatro primeros congresos (1919-1922). Madrid: Fundación Federico Engels.