Imperialism and Revolution / Episode #34

Decisive revolutionary steps

April 9, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

The July 26 Movement rose to power on the basis of its promise to establish a revolutionary government what would defend the needs of the people, leaving behind historic tendency for governments to give priority to the interests of the economic and financial elite. It had to deliver on that promise in order to maintain the overwhelming and enthusiastic support by the people that it enjoyed.

The Provisional Revolutionary Government established on January 2, 1959 was a coalition government of anti-Batista forces. Fidel declined to enter the Council of Ministers, which named him Chief of the Armed Forces. During the month of January, the government was slow and inefficient in the adoption of reform measures. Some members of the Council of Ministers approached Fidel and persuaded him to assume the position of Prime Minister, whose designation to the position was unanimously approved by the Council on February 16.

On that same day, the Council approved Fidel’s proposal for a reduction in the salary of the ministers by 50%. The Council of Ministers also approved on February 16 measures that were designed to protect employment, including: a ban on the dismissal of public employees; suspension of the dismissal of employees in the private sector, when this had been done to reduce costs; and restoration of employees that had been dismissed for this reason. These measures responded to the anxieties of the people. In previous changes of government, there had been massive and arbitrary dismissal of public employees, in order to facilitate nepotism and the fulfillment of commitments made during electoral campaigns. In numerous personal meetings with the people during the month of January, Fidel had found that unemployment was among the highest concerns, and there was fear that the changing political situation could provoke the elimination of jobs.

On February 17, the Council of Ministers approved a law that made legal all acts that had been prosecuted as criminal acts during the period of March 10, 1952 to December 31, 1959, when such acts were part of the movement against the Batista dictatorship.

On February 20, in response to efforts to create disorder by instigating peasants to occupy land, the Council approved a law stipulating that all persons who occupy land without waiting for the enactment of an agrarian reform law would forfeit their right to receive land under said law.

On February 28, the Council approved a law proposed by Faustino Pérez, Minister of the newly created Ministry for the Recuperation of Embezzled Public Funds, confiscating the property of Batista and persons associated with the Batista regime. The law affected the property of Batista and his collaborators, including: officials of the armed forces that had participated directly in the coup of March 10, 1952; ministers of the Batista government during the period 1952 to 1958; members of the bogus Congress of 1954-58; and candidates in the sham elections of November 1958.

On March 3, the Council took action against the Cuban Telephone Company, a US-owned company that had been operating in Cuba since 1909. It approved a law authorizing government intervention in the affairs of the company, and it annulled an increase in telephone service rates that had been implemented since March 13, 1957.

On March 19, the Council approved a law that reduced housing rents. A scale was established, with the lowest rents reduced to 50% and the highest rents reduced to 70% of their previous level.

On April 21, the Council abolished beach concessions to persons and societies of recreation, which since 1890 had blocked public access to the beaches. The Council’s action of April 21 returned the beaches to the people.

The most significant step of 1959 was the Agrarian Reform Law of May 17. Agrarian reform had been a central proposal of the July 26 Movement since 1953. Following the triumph of the Revolution, Fidel met discretely on a regular basis with a small group in the house of Ernesto “Che” Guevara in order to formulate an agrarian reform proposal. In addition to Fidel and Che, the group of seven persons included Vilma Espín, who later became Founding President of the Federation of Cuban Women; and Antonio Núñez Jiménez, who would become a well-known and respected adventurer, ecologist and writer.

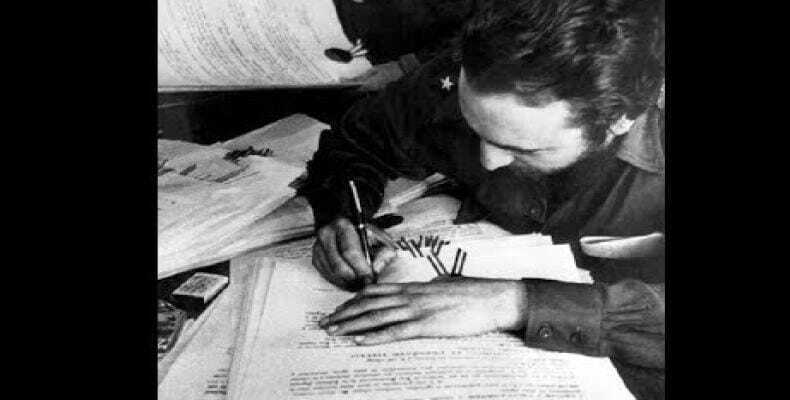

The Agrarian Reform Plan that was developed by Fidel’s group was presented to the Council of Ministers on April 28. The Agrarian Reform Law was signed by the Council on May 17, in commemoration of the date in 1946 of the assassination of Niceto Pérez, a peasant who had defied the government of Ramón Grau by occupying and cultivating land belonging to the state. The signing ceremony was held in the wooden shack that had been Command Headquarters of the guerrilla army in the Sierra Maestra.

In the May 17 signing ceremony, Fidel declared that the Agrarian Reform Law “will give the country a new economic and social order, creating and developing new sources of work to the benefit of the poorest and dispossessed social classes, of the peasant and working class, forgotten by previous governments.” In addition, the Council created the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, and it named Antonio Núñez Jiménez, one of Fidel’s small group, as its Executive Director. Following the ceremony, Fidel addressed the nation via Radio Rebelde, proclaiming that the law “initiates an entirely new stage in our economic life.”

The Agrarian Reform Law of 1959 abolished large-scale landholdings, tenant farming, and sharecropping. It established a maximum limit 1,340 hectares for sugar or rice plantations or cattle estates. In accordance with the law, the government subsequently confiscated the land of 4,423 plantations, distributing it to peasants who had worked on it as tenant farmers or sharecroppers, and establishing state-managed farms and cooperatives. The former owners were offered compensation, based on the assessed value of the land for taxation purposes, and with payment in the form of twenty-year bonds. Inasmuch as some US-owned plantations covered land of 200,000 hectares, the law had a significant effect on the Cuban structure of land ownership and distribution. It provided the foundation for a fundamental transformation in the quality of life of the rural population that endures to this day

The Agrarian Reform Law of 1959 was the defining moment of the Cuban Revolution. It was a radical step that constituted a definitive break with the landholding class, both Cuban and international. It was a necessary step, inasmuch as the unequal distribution of land was one of the structural sources of extensive poverty. A government committed to the people must take land from the national estate bourgeoisie and transnational corporations; it must establish alternative land-use patterns and alternative patterns of land distribution that are able to promote and sustain national development. With the enactment of the Agrarian Reform Law, the radical and anti-neocolonial character of the Cuban Revolution were made manifest. As Cuban scholar Jesus Arboleya wrote nearly a half century later, the Agrarian Reform Law “showed that the [political] balance was inclined irremediably toward the most radical sectors,” and it “defined the anti-neocolonial character of the revolution.”

The Revolution sought to leave behind Cuba’s peripheral role in the capitalist world-economy, to which it had been assigned by Spanish colonialism and U.S. neocolonial domination, and in which Cuba produced sugar for export, on a base of cheap, superexploited labor, leaving the agricultural workers in wretched poverty, and leaving the nation without an sufficient market to sustain industrial development. The Revolution envisioned a different kind of participation in the world-economy, based on industrial and scientific development, with a highly educated work force. Accordingly, Fidel declared on January 15, 1960, that “the future of our country has to be necessarily a future of men and women of science; it has to be a future of men and women of thought.”

This commitment constituted the foundation for the development of a comprehensive and universally accessible educational system and for the creation of scientific research institutions integrally tied to industrial and agricultural production and to the providing of medical services, which included the establishment of the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, the research center that created the Interferon Alfa-2B compound, a drug that is fabricated and marketed by the Cuban National Center for Biopreparation and by the Chinese-Cuban mixed company Changchun Heber Biological Technology. Interferon Alfa-2B is today an important weapon in the global war against the Covid-19 pandemic.

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Sources

Arboleya, Jesús. 2008. La Revolución del Otro Mundo: Un análisis histórico de la Revolución Cubana. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Buch Rodríguez, Luis M. and Reinald Suárez Suárez. 2009. Gobierno Revolucionario Cubano: Primeros pasos. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

Castro, Fidel. 2006. Cien Horas con Fidel: Conversaciones con Ignacio Ramonet. La Habana: Oficina de Publicaciones del Consejo de Estado. [English translation: Ramonet, Ignacio. 2009. Fidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken Autobiography. Scribner.