Even with the limited resources imposed by the U.S. blockade, Cuba pays special attention to people affected by ataxia, a disease that still has no cure and is characterized by coordination, balance, gait and language disorders, which worsen over time.

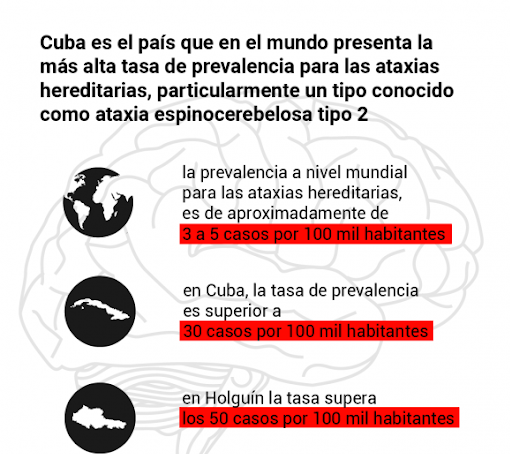

According to experts, there are 50 known molecular forms of Spinocerebellar ataxias in the world. Cuba is the country with the highest number of patients with type 2, one of the most frequent in the world.

According to specialists, there are 36.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in Cuba, although its frequency in the eastern province of Holguin is 183 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

The country makes available, free of charge and universally, the existing therapies for people who suffer from this neurodegenerative disease or are at genetic risk of being affected.

But its scientific community also works tirelessly to create drugs to slow the progression of the disease and improve the quality of life of patients.

NeuroEpo, a molecule developed by the Center for Molecular Immunology and which is being applied in the country to different neurodegenerative diseases, is part of that effort.

A phase III clinical trial is currently being conducted in several Cuban provinces to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the nasal application of NeuroEpo in adult patients with Spinocerebellar ataxias.

Trials I and II took place between 2015 and 2016, the results of which evidenced an improvement of the cerebellar syndrome and cognitive manifestations. It also showed a high safety profile of NeuroEpo.

This drug is a hope for patients with this disease, and another example of the country's effort to advance in the search for new treatments, in which the CIRAH, Carlos J. Finlay Center for Research and Rehabilitation of Hereditary Ataxias, undoubtedly plays an essential role.

An institution that combines medical assistance with scientific research and whose results have a direct impact on Cuban families where the disease is present.

The dedication of our scientists and the political will of the government over the years has made it possible for Cuba to have epidemiological studies, biomarkers to characterize the condition and its progression, as well as prenatal and presymptomatic diagnosis programs, the only ones of their kind in Latin America.