By Maryam Qarehgozlou / PRESS TV

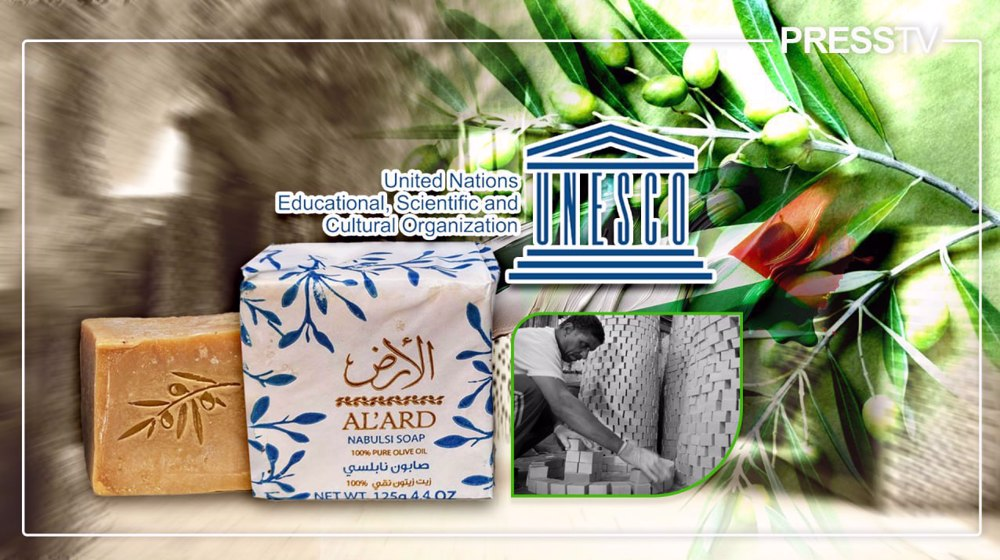

In a moment of historic recognition, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has inscribed Nabulsi soap-making onto its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

During the 19th session of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, held in Asunción, Paraguay, from December 2 to 7, the centuries-old Palestinian tradition was hailed for its cultural value and enduring legacy.

Deeply rooted in the land and spirit of the city of Nablus in the occupied West Bank, this cherished craft reflects the profound connection between people and their land.

Today, it stands among the world's treasured cultural assets and is a testament to the resilience and richness of the Palestinian heritage that has been overshadowed by war and occupation.

Nabulsi soap, named after the city of Nablus in the occupied West Bank, is crafted using three locally sourced ingredients: olive oil, water, and lye, and has gained a reputation for being the symbol of Palestinian resilience and artistry.

The Palestinian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates issued a statement on Tuesday, hailing the UNESCO listing of the Nablusi soap.

The ministry said the recognition brings global attention to the rich cultural heritage of the Palestinian people, despite ongoing attempts by the Israeli regime to undermine and erase their identity.

“[The inscription] enhances recognition of Palestinian culture and its traditional crafts rooted as part of human history, and preserve them from extinction and from Israeli attempts to obliterate the cultural identity of the Palestinian people and falsify Palestinian history and narrative,” it stated.

The ministry further noted that Nablus soap is one of the most distinctive cultural and historical emblems of Palestine, and deeply entrenched in Palestinian cultural identity, transcending its status as merely a handicraft and embodying an enduring symbol of the nation’s heritage.

“The tangible and intangible Palestinian cultural heritage is a testament to the authenticity and depth of the Palestinian people’s connection to their land and heritage since ancient times,” it stated.

The ministry urged all nations and international actors to protect the Palestinian people, heritage, culture, and history from “the ongoing Israeli genocide against Palestinians” and to work to uphold the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people, including their cultural rights.

According to UNESCO, the Nabulsi soap, a hand-crafted product originating from Palestine, is meticulously made in a process that commences after the yearly olive harvest. Artisans meticulously craft the soap and imprint their family’s distinctive seal before packaging and aging it for a full year, it added.

“Most families in Palestine share the tradition, with both men and women taking part in all stages of the production process and children helping their parents cut and pack the soap,” UNESCO noted.

Nabulsi soap-making serves as a vital source of livelihood for the families engaged in this traditional craft and the knowledge and skills associated with this practice are transmitted from generation to generation through hands-on learning in farm settings, olive presses, and within the intimate confines of family-run workshops, it further added.

The UN cultural body also said it included soap making on its heritage list in recognition of its social significance. “The use of olive oil reflects people’s strong relation to nature, and many people use their homemade soap as a personal gift for celebrations such as weddings and birthdays," it noted.

"Often, soap makers give soaps to visitors to take home. The element encourages dialogue while connecting family members and communities.”

Numerous organizations and educational initiatives play a crucial role in promoting and teaching this traditional craft to wider audiences, within and outside the city of Nablus. Additionally, the art of soap-making has experienced heightened visibility and recognition through various channels, including films and social media platforms, which have helped raise awareness and appreciation for this cherished cultural practice.

Nablusi soap is made from just three primary ingredients: olive oil, water, and lye. Unlike many commercial soaps, Nablus soap contains no artificial additives, colors, or fragrances.

The operational Nablus soap factories that remain today, have largely preserved the traditional manufacturing process established two centuries ago, with only minor modifications.

This process consists of five stages—cooking, laying, cutting, drying, and packaging—executed by four teams of workers.

On the ground floor of the factory, the primary ingredient, olive oil, is mixed with caustic soda and water in a large bowl (called halla in Arabic) and undergoes a three-day “cooking” process.

Upon completion, the team leader assesses the quality of the soap by tasting it or crumbling it in their hand. The mixture is then transported in buckets by porters and poured onto a designated section on the first floor (mafrash), where it is left to dry for a day.

Subsequently, the soap is formed into small cubes, imprinted with the factory’s brand, and meticulously cut by a team of three to four skilled workers.

After cooking the soap, the misxture is transported in buckets by porters and poured onto the floor. The following day, these same workers stack the soap pieces into pyramids (tananir), allowing them to dry for two to three months.

Finally, another team packages the soap, wrapping it in paper emblazoned with the factory’s branding. These workers can package approximately 500 to 1,000 bars of soap per hour.

At the pinnacle of Nablus soap production, factories were registered companies with distinct brand names and logos on the soap’s wrapping paper.

These brands often incorporated symbols or animal names, such as muftahein (the two keys), al-jamal (the camel), al-na‘ama (the ostrich), al-najma (the star), al-baqara (the cow), al-badr (the full moon), and al-assad (the lion).

Additionally, slogans such as “Nablus soap extra” (al-sabun al-Nabulsi al-mumtaz) or “the well-known” (al-ma‘ruf) were featured on the packaging to distinguish and promote their products.

The tradition of soap-making has ancient roots in the West Asia region in general and Palestine in particular, with olive oil serving as its primary ingredient.

The 12th century marked a significant period for the evolution of soap-making, with the Arab region emerging as a prominent hub for the exquisite craft.

Arab artisans gained widespread recognition for their expertise in producing aromatic and high-quality soaps, distinguishing them from their European counterparts, who primarily manufactured less pleasant varieties.

This divergence in quality even led to a linguistic legacy, as the Arabic term ṣābūn and the Latin word sāpō were adopted into numerous languages to denote soap.

The craft of soap-making in Nablus can be traced as far back as the 10th century.

According to the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, soap-making was initially a domestic practice, but it eventually expanded to urban hubs, including Aleppo in Syria, Tripoli in Lebanon, and Nablus in Palestine, where it gained prominence.

The art of soap-making in Nablus dates back to the 10th century, according to historians.

Nablus’ renowned olive oil soap transcended borders, finding its place in markets throughout the Arab world. Remarkably, during the Crusades, this esteemed product even managed to traverse continents, purportedly capturing the admiration of Queen Elizabeth the First of England.

In the Ottoman era, influential families of the urban elite acquired major soap factories in central Nablus.

By the nineteenth century, the soap industry had transformed into the city’s leading economic sector, with ownership of a soap factory emerging as a symbol of affluence, social standing, and a strong connection to urban life.

The story of olive oil soap production in the occupied West Bank city of Nablus is one of resilience in the face of numerous challenges. Soap makers in this region have persevered through various hardships, including natural disasters and the persistent strain of the Israeli military occupation and daily atrocities, demonstrating an unwavering commitment to their craft and cultural heritage.

At the peak of its prosperity around 1907, some 30 Nabulsi soap factories in the city were responsible for providing half of all soap in Palestine, a testament to the industry’s vitality and the product’s widespread popularity.

However, the industry faced a decline due to a series of challenges, including the catastrophic 1927 Jericho earthquake, the arrival of Jewish settlers in the 1920s, and, later, the onset of Israeli military occupation of the Palestinian territories in 1948.

These events contributed to shifting socio-political dynamics that adversely impacted the once-thriving soap-making tradition of Nablus.

The absence of a sovereign state capable of controlling borders and taxes and the lack of legal protection for the name “Nabulsi” which caused cases of counterfeiting, left Nabulsi soap vulnerable to external pressures.

Compounding this challenge, the British Mandate offered customs advantages to Zionist traders, while Egypt and Syria enacted protective measures to shield their domestic production. These factors converged to create an unleveled playing field for Nabulsi soap makers. Moreover, following the onset of the First Palestinian Intifada (1987-1993), maintaining soap production in Nablus became increasingly difficult.

The Israeli military attacks disproportionately targeted the Old City of Nablus, a historically significant area where many soap factories were situated.

As a result, numerous soap factories were forced to shut down during the 1990s, further challenging the preservation of this important cultural practice.

During the early years of the Second Palestinian Intifada (2000-2005), Nablus faced a severe Israeli military lockdown. Checkpoints choked off access to the city, hindering movement, and lengthy curfews became commonplace.

While the 1927 earthquake had already damaged soap factories within and surrounding the historic city, it was the intense Israeli bombardment of the Old City and the forced closures during the Second Intifada that pushed the soap industry in the region to the brink of collapse.

Of the over thirty soap factories that once thrived in Nablus’ Old City, several sustained damage during the Israeli military incursion in 2002, with two factories completely destroyed.

Since 2007, only two soap factories have remained operational in Nablus, which belong to the Tuqan and Shaka’a families.

The majority of the remaining factories have since been abandoned or repurposed, leading to a decline in the region’s once-flourishing soap industry.

Since 2007, only two soap factories have remained operational in Nablus, which belong to the Tuqan and Shaka’a families, who maintain them as a heritage.

These factories export the vast majority of their production to Jordan, taking advantage of long-standing relationships with the distributors on the East Bank of the river and the Palestinian population in the country. A small part of the production is also sent to Kuwait and the Persian Gulf states.

Despite the damage inflicted upon numerous soap factories in Nablus during the decades-long Israeli occupation of the Palestinian lands, local artisans have worked tirelessly to keep this cultural heritage alive.

Today, Palestinians say Nablus soap is more than just a product: it is a symbol of resilience and identity for them shared with the world.