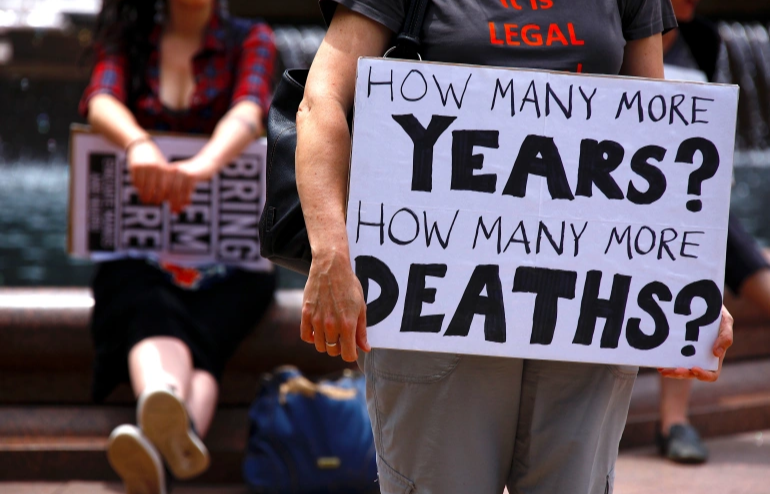

Refugee advocates hold placards as they participate in a protest in Sydney, Australia, against the treatment of asylum seekers at Australia-run detention centres located at Nauru and Manus Islands. [File: David Gray/ Reuters]

Sydney, December 23 (RHC)-- An Afghan refugee held in Australian immigration detention, Jamal set himself on fire in 2019 in front of medical staff and security personnel at the offshore detention facility on the Pacific Island of Nauru.

Jamal had come to Australia by boat in 2013, fleeing persecution in his home country. He had worked as an interpreter with Western forces in Afghanistan. But under Australian immigration policy, he was moved to the Nauru detention facility.

When he self-immolated in 2019, it was out of desperation after five years of indefinite detention. “Life was really hard there for me,” he told Al Jazeera, “and we didn’t have any hope.” Jamal has now been held in Australian immigration detention for almost nine years.

Following the self-immolation, he was moved to a hospital in the Australian city of Brisbane and is now being held at a hotel in the country’s second-largest city, Melbourne. The hotel made headlines earlier in the year when nearly half of the refugees held there contracted COVID-19. His lawyers now fear he may be moved back to Nauru.

When he was first sent to Nauru in 2013, refugees on the island were housed in tents in closed camps. These camps made headlines repeatedly for their inhumane conditions, from dilapidated housing facilities to rape and sexual assault.

Over the years, the camps were opened up, and the refugees began to be allowed into the broader island of Nauru, but this carried its own dangers and stressors, said Jamal. “Nauru is a tiny island,” he said, “it’s a really tiny island. It’s like a prison for us where you can’t move, [you’re] just stuck.”

Refugees faced serious violence from locals, he said — they were beaten, bullied, and attacked. This violence has been widely documented. One report from Amnesty International in 2016 recorded cases where locals “cursed and spat” at refugees, “threw bottles and stones, swerved vehicles in their direction as they walked or rode on motorbikes”.

The Australian government was “well aware of the abuses on Nauru” the report said, with countless human rights groups — and even a Senate Select Committee and a government-appointed independent expert — highlighting the issue.