The legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

By Charles McKelvey

June 10, 2020

Slavery in the U.S. South functioned to provide cheap labor for the production of cotton; and the post-slavery system of low-waged tenant farming and sharecropping, supported by Jim Crow segregation, possessed the same economic functionality. However, during the course of the twentieth century, Jim Crow segregation became dysfunctional, because of its incompatibility with the U.S. role as the leading nation in a neocolonial world order.

The African-American movement discerned the objective possibilities created by the increasing dysfunctionality of Jim Crow. The movement originally developed in the urban North, where blacks had migrated in large numbers beginning in 1917, pulled by factory jobs created by World War I. In the 1920s, in addition to demanding civil and political rights, the movement advocated self-government for peoples of color in Africa, Asia, West Indies, and the United States. From the period of 1930 to 1955, the movement adopted a strategy of mass action, including demonstrations, rallies, and boycotts, in support of civil, political, economic, and social rights, seeking to pressure the federal government. In the 1940s, it attained presidential executive orders banning racial discrimination in defense industries, federal government employment, and the armed forces. At the same time, the movement used the U.S. legal system to challenge the constitutionality of state-mandated segregation in education in the South, which culminated in a 1954 Supreme Court decision ruling that segregation in schools violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Beginning in the 1930s, various factors were changing the economic and social landscape of the South. The Roosevelt administration had adopted several effective measures that were designed to promote the industrialization of the South, in response to the increasing impoverishment of the region. The industrialization of the South stimulated black rural-to-urban migration in the South, leading to a strengthening of black churches, black colleges, and black protest organizations.

The industrialization and urbanization of the South created the conditions that made possible the application of the mass action strategy, previously applied only in the North. In the period 1955 to 1965, mass action was carried out in various cities of the South, putting forth demands such as the desegregation of buses, lunch counters, and stores as well as the right to vote. The movement was led by college-educated black ministers and black students. Major events of the period included the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-1956, the student sit-in movement of 1960, the freedom rides of 1961, the Birmingham campaign of 1963, the March on Washington of 1963, Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, and the Selma voting rights campaign of 1965.

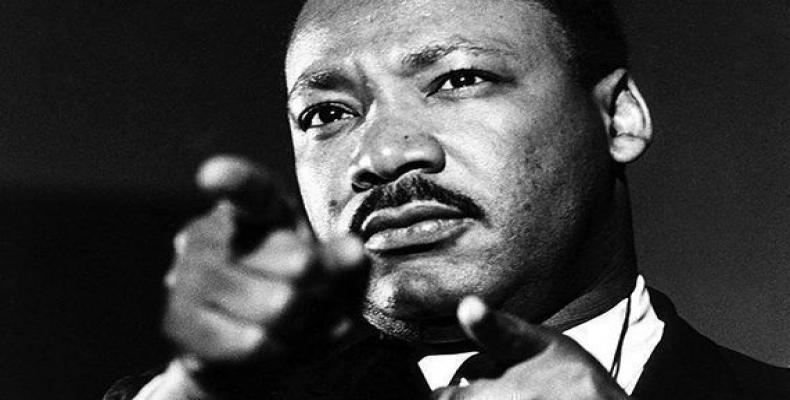

During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the black ministers leading the movement formed the Montgomery Improvement Association, electing Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as its president. The son of a prominent minister in the Atlanta black community, the 26-year-old King had recently been named pastor at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery. He had graduated from Morehouse College, a prominent historically black college in Atlanta, at the age of 19. He had obtained a divinity degree at Crozier Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he studied the teachings of Gandhi and the social gospel theological tradition of American Protestantism; which was followed by a Ph.D. in religion from Boston University. During the mass meetings, King quickly established himself as an eloquent and powerful speaker, defending the righteousness of the boycott as fully in accordance with the principles of American democracy and Christianity.

The direct-action strategy of 1955 to 1965 attracted national and international media attention, and it compelled the federal government to take the side of the movement. The Civil Rights Law of 1964 prohibited racial discrimination in employment and in public accommodations. The Voting Rights Law of 1965 established effective measures for the protection of black voting rights. These laws were effective in creating a new reality defined by the protection of the political and civil rights of blacks. However, the laws did not address the protection of social and economic rights; they had no provision for the elimination of the social and economic inequalities that had been created by decades of discrimination.

For King, the historic moment meant that the civil rights movement was reaching a second stage, in which the focus would be on the attainment of social and economic rights. As early as 1963, King had become aware that white allies were not prepared to support the movement in this second stage. When it came to calls for equality in jobs, housing, and education, white allies disappeared.

In 1964, King wrote of a need for some form of compensation for blacks and lower-class whites, which he called a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged.” It would include preferential treatment in education and employment as reasonable compensation for past discrimination.

In 1967, King wrote that the lack of support by white allies had the consequence that the economic program passed by the Congress was inadequately funded. The failure of the federal government to support the second phase of the movement, he maintained, had given rise to black anger and despair, expressed in urban rebellions and in the “Black Power” slogan.

In the last year of his life, King developed an increasingly internationalist vision. In three key addresses in 1967, King declared his opposition to the Vietnam War. He maintained that U.S. policy in Vietnam had violated the principle of self-determination, and it reflects a new form of colonialism. The United States, he declared, is trying to roll back the clock and perpetuate white colonial domination of people of color. The United States has developed [he said] a “pattern of suppression” of the Third World; the United States is on “the wrong side of a world revolution.” He declared: “These are revolutionary times. All over the globe men are revolting against old systems of exploitation and oppression. . . . The shirtless and barefoot people of the land are rising up as never before. . . . We in the West must support these revolutions.”

In 1968, King envisioned the Poor People’s Campaign, a campaign of lobbying and aggressive non-violent action that would compel the federal government to take action with respect to jobs and income for all Americans. King sought to forge a coalition with poor whites demanding economic justice, focusing on common economic interests.

In the period 1964 to 1968, therefore, with his famous March on Washington “I Have a Dream” Speech in the past, Martin Luther King proposed a multiracial coalition to pressure the U.S. government to act in defense of the social and economic rights of all citizens, and to lead the nation’s public discourse toward an anti-imperialist foreign policy. This was a realistic proposal, consistent with U.S. conditions and possibilities. Indeed, it was the necessary road for the nation, inasmuch as its global hegemony was no longer sustainable, and the world-system itself was entering a sustained crisis that made structural change necessary.

But the U.S. power elite was morally and intellectually unprepared for the historic moment. It rejected King’s proposal. It adjusted to national and global realties by taking the nation and the world to the Right, beginning in 1980. The neoliberal turn has deepened the crisis of the world-system, and it has accelerated U.S. decline. These developments have made King’s proposal more necessary and more urgent than ever.

Paul Simon was not entirely right. The words of the prophets are not always written on the subway walls. Sometimes they are articulated by leaders with an exceptional capacity to discern the necessary road, lifted up by the people to speak in their name. Have we forgotten the prophetic words of that powerful voice that we once called the “King of Love?”

References

King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1958. Stride toward Freedom. New York: Harper & Row.

__________. 1964. Why We Can’t Wait. New York: Harper & Row.

__________. 1966. “The Last Step Ascent.” The Nation 202:288-92.

__________. 1967. Address at the April 15 Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, United Nations Plaza, April 15. The King Papers, Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Non-Violent Social Change, Atlanta, Georgia.

__________. 1967. “Beyond Vietnam.” Speech to Clergy and Laity Concerned About the War in Vietnam, Riverside Church, April 4. The King Papers, Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Non-Violent Social Change, Atlanta, Georgia.

__________. 1967. “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam.” Address at the Nation Institute, Los Angeles, California, February 25. The King Papers, Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Non-Violent Social Change, Atlanta, Georgia.

__________. 1968. Where Do We Go from Here? New York: Bantan Books.