Imperialism and Revolution

Episode #30

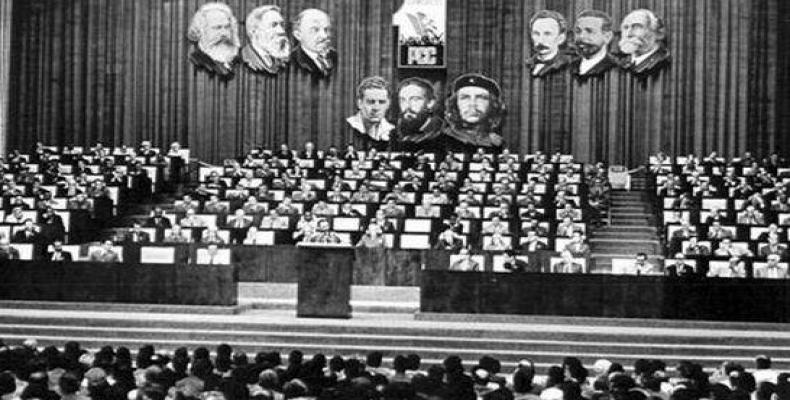

Marxism-Leninism with a Fidelist stamp

March 19, 2020

By Charles McKelvey

In Fidel’s first years in the University of Havana, he was tied to an opposition party, the Orthodox Party, officially named the Party of the Cuban People, which emphasized criticism of the corruption, fraud, and embezzlement of funds of the Batista and Grau governments. However, as a result of his reading of Marx, Engels, and Lenin, beginning in his third year at the university, Fidel’s ideas had moved beyond the positions of the Orthodox Party. He came to appreciate the role of class divisions in human society, which explained to him the reasons why politicians do not represent the interests of the people, even when they are elected by the people. That Marxist literature, Fidel said in an interview more than thirty years later, attracted him profoundly; it was a true political revelation. As a result of this intellectual conversion, Fidel arrived to understand that, although the Orthodox Party had tapped into popular discontent, it did not attribute responsibility for the problems of the people to the capitalist system and to imperialism.

In addition, as a result of his intellectual conversion to Marxism-Leninism, Fidel could see more deeply the confusions of the people. The people suffered from poverty, injustice, and inequality; and Fidel could see that the mass of people was discontent. The people, however, did not understand the essence of the social problem. They attributed unemployment, poverty, and the lack of schools and hospitals to corruption and embezzlement of funds, to the perversity of the politicians.

Fidel had good relations with the leaders of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), and they were allies in nearly all the struggles of the moment. However, in spite of this, and in spite of Fidel’s intellectual conversion to Marxism-Leninism, Fidel did not join the PCC. Instead, he worked on forging a radical faction in the Orthodox Party.

Fidel saw that Cuban communists were isolated as a result of the influence in Cuba of imperialist ideas and McCarthyism. The communists had attained influence among the workers as a result of working with them; they had much prestige among the workers. But there were prejudices against socialism and communism transmitted through the media of communication. The media preached against socialism everywhere: on radio and television, in the cinema, books, magazines, and the daily press. They invented the most absurd things to poison the people against socialist ideas. The result was that the people had distorted ideas concerning socialism, except for workers with whom the PCC had worked, and this limited, in Fidel’s view, the practical political possibilities of the Communists.

Moreover, Fidel and the Cuban Communist Party had different understandings concerning how to respond to the confusions of the people. The Party believed in the patient organization and education of the people, gradually bringing them to a more mature political consciousness. But Fidel believed that, because of their profound and pervasive discontent, the people constituted a great potentially revolutionary mass. He believed that there existed the possibility of acting with that great potentially revolutionary mass. Accordingly, Fidel formulated the theory that the people have to be brought to revolution in phases, in stages, step by step. He conceived of a platform of proposals that was not yet a socialist program and that did not declare itself socialist; rather, it focused on proposing solutions to the various social problems that the people confronted. A platform capable of attaining the support of the great mass of the population, as a prelude to socialism. Fidel saw his revolutionary plan as in contradiction with the strategies of the PCC. He did not believe that he would have been able to convince PCC leaders of the correctness of his ideas, and for the most part he did not try. Instead, he was oriented to working with the youth of the ranks of the Orthodox Party, to which he had been tied since his first days at the University of Havana.

Fidel arrived to his revolutionary plan not too long after his graduation of from the University of Havana in 1950. His conception went beyond the Orthodox Party, which did not have an explanation of the sources of the social problems, nor did it have a plan for bringing the people gradually to revolution. But Fidel sensed that some youth in the Party were prepared for the concept. He proceeded to implement the plan, launching a campaign against injustice, poverty, unemployment, high rents, evicted peasants, low salaries, political corruption, and heatless exploitation that was everywhere to be seen. He began not by preaching socialism as an immediate goal. He proposed a program for which the people were prepared, from which they would begin to act and move toward a truly revolutionary direction. These proposals eventually became the Moncada Program expressed on October 16, 1953 in his self-defense before the Court, later known as History Will Absolve Me. But the program had been formulated prior to the Batista coup d’état of March 10, 1952.

The Batista coup changed everything. Fidel turned to the idea of the armed struggle in order to overthrow the dictatorship and reestablish constitutional order, which was a concept that was embraced by many political and social leaders in the aftermath of the coup. Fidel, however, combined the concept of armed struggle with the radical social platform that he had formulated during his work with the radical youth of the Orthodox Party.

Following the coup, Fidel began to organize combat cells from the youth of the ranks of the Orthodox Party, beginning the organizational preparation for the July 26, 1953 attack on Moncada Barracks. In fourteen months, he and several compañeros had organized 1200 men and women, creating a disciplined and determined organization.

Subsequent events are well known to history. Fidel was sentenced to imprisonment for fifteen years on the Isle of Pines for his organization and leadership of the attack on the Moncada Barracks of July 26, 1953. He and his companions were released on May 15, 1955, as a result of a popular amnesty campaign. Following his release from prison, Fidel continued to work on putting into practice his revolutionary plan. The July 26 Movement was established on June 12, 1955, under the direction of a small group of trustworthy and capable leaders, led by Fidel, who then went to Mexico to organize the armed struggle. On December 2, 1956, Fidel and 81 armed guerrillas, having trained in Mexico and having traveled by sea for seven days, disembarked from the yacht “Granma” in a remote area of eastern Cuba, with the intention of establishing an armed struggle in the mountains known as the Sierra Maestra.

The strategy of an armed struggle that moved from the mountains to the plains to the cities and that advocated a radical program of social and economic measures that did not declare itself socialist was not a strategy that was embraced by the Communist Party. It had emerged as a result of Fidel’s creative application of the concepts of Marxism-Leninism to the political and ideological conditions of Cuba.

As he embraced the revolutionary ideas of Marxism-Leninism and adapted them to Cuban conditions, Fidel remained a disciple of Martí. Like Martí, he believed in heroism, and he saw commitment to truth as the highest duty. He interpreted the Moncada attack as a courageous, heroic, and patriotic action, carried out in the name of Martí. Like Martí, he believed that courageous action can change the political landscape, making possible what had previously appeared impossible, and accordingly, he possessed Martí’s faith in the future of humanity. And like Martí, his principal devotion was to the homeland and to the nation; to die for the nation, he believed, was to live. He saw the Cuban struggle as a struggle for social transformation and for the sovereignty of the nation and against the neocolonial intentions of the United States, as did Martí.

In his 1985 interview with Brazilian Dominican Frei Betto, Fidel declared, “I believe that my contribution to the Cuban Revolution consists in having realized a synthesis of the ideas of Martí and of Marxism-Leninism, and having consequently applied it in our struggle.”

This is Charles McKelvey, speaking from Cuba, the heart and soul of a global socialist revolution that struggles for a more just, democratic, and sustainable world.

Sources

Castro, Fidel. 1985. Fidel y La Religión: Conversaciones con Frei Betto. La Habana: Oficina de Publicaciones del Consejo de Estado. [English translation: Fidel and Religion: Conversations with Frei Betto on Marxism and Liberation Theology. Melbourne: Ocean Press].