Revolution, counterrevolution, and emigration

by Charles McKelvey

March 6, 2020

It was not absolutely necessary for the United States of America to confront and attempt to destroy the triumphant Cuban Revolution in 1959. An alternative road was possible, involving cooperation between the imperial giant and its former neocolony, taking concrete and exemplary steps toward an alternative world-system not founded on colonial domination and superexploitation, but based instead on cooperation and mutually beneficial trade among nations. Indeed, Franklin Delano Roosevelt had envisioned such a post-World War II world, in which the colonial empires would no longer be, the colonies would become independent nations, and every citizen of the world would live in what he called “freedom from want,” that is to say, with their fundamental human needs met.

But in the late 1940s, the Truman Administration cast aside FDR’s internationalist vision and took a nationalist approach to the post-World War II economy. The Truman Administration was oriented to the defense of U.S. imperialist interests throughout the world and the creation of a permanent war economy. To justify and legitimate these policies, the Cold War ideology was constructed, which falsely portrayed the foreign policy of the Soviet Union as expansionist, and which distorted and exaggerated the undemocratic dimensions of the Soviet political-economic system. Meanwhile, the European colonial empires were collapsing, compelled to concede political independence to anti-colonial movements in the colonies, a phenomenon that was giving new economic opportunities to the imperialist intentions of the ascending United States. What emerged was a neocolonial world-system with the United States as the hegemonic power, and with the Soviet Union as a second superpower, with its potential to threaten U.S. interests in various regions in the world constituting the basis of U.S. foreign policy.

From a political vantage point premised on defense of the neocolonial world-system and U.S. hegemony, the U.S. power elite was obligated to confront and destroy the Cuban Revolution, inasmuch as it was and is in essence an anti-neocolonial revolution, seeking to defend the sovereignty of the Cuban nation.

From the beginning, the U.S. administration adopted a policy of stimulating Cuban emigration through the indiscriminate application of the “political refugee” category for the majority of immigrants proceeding from Cuba. The very first immigrants following the triumph of the Revolution could reasonably be considered political refugees, since in many cases it was a question of persons of the Batista dictatorship that fled to the United States. But they soon were joined by nearly the entirety of the national oligarchy and the rest of the more privileged sectors, who in fact were not politically persecuted in Cuba. To the contrary, they were entreated to join the revolutionary project, lending their enterprises and their skills and services to the development of the Cuban economy in the new revolutionary stage. The U.S. portrayal of these second wave emigrants as political refugees had evident advantages from the point of view of political propaganda, which colored them as victims of a tyrannical communist regime, seeking liberty in the democracy of the United States.

The stimulation of Cuban emigration also functioned to deprive the Cuban revolution of qualified personnel, needed for the functioning of the Cuban economy. The great majority of Cuban emigrants to the United States during the period 1959 to 1962 were owners of landed estates and industries, businesspersons, merchants, technicians, professionals, and state employees; and the family members of same. The percentages of these employment categories in the Cuban emigration were approximately three times their proportion of the population of Cuba. And the emigrants had much higher levels of education than the Cuban population.

At the same time, the stimulation of Cuban emigration functioned to establish the social base that would sustain the counterrevolutionary movement. As Jesus Arboleya has written, “The Cuban emigrants became the fundamental component of the political opposition to the Revolutionary Government. This political function of the Cuban emigration in the United States established a mutual beneficial relation between the émigré community and the U.S. government, which explains the persistent priority of the Cuban problem in the political agenda of the émigrés as well as the extraordinary facilities that the U.S. government gave to this immigrant group.”

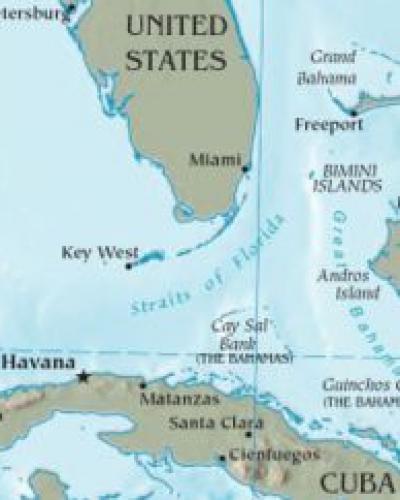

The first counterrevolutionary organizations operating from Miami were formed in 1960, and they were composed of members of the national bourgeoisie, persons affiliated with the Batista regime, representatives of the traditional political parties, and Catholics influenced by the anti-Communist ideology. By 1962, the U.S. government no longer directly supported internal clandestine groups in Cuba, which had been nearly totally dismantled by Cuban popular militias; rather, the U.S. committed itself entirely to the use of the Cuban émigré community as the base of the Cuban counterrevolution. In accordance with this strategy, in 1962 a special unit of the CIA created approximately 55 legitimate companies in Florida that supported covert counterrevolutionary activities in Cuba. During the period, the CIA directly and indirectly financed and supplied counterrevolutionary groups in Miami that were engaging in counterrevolutionary activities in Cuba, including sabotage of the Cuban energy, transportation, and production infrastructure.

Such injection of resources by the CIA was the base for the economic development of the Cuban-American community in Miami. Taking into account the different privileged and relatively privileged social sectors that comprised the counterrevolutionary organizations in Miami, the U.S. government’s financial investment in the community had the consequence of forging a political and social integration of the different economic and social sectors that had an economic or political interest in the overthrow of the Cuban Revolution, thus facilitating the re-composition of the Cuban national bourgeoisie and other privileged sectors into a Cuban-American bourgeoisie.

The preferential treatment that Cuban immigrants received in a highly developed society like the United States facilitated continued Cuban emigration to the United States during the 1960s and 1970s, both legal and illegal, representing the especially privileged sector of white Cuban society. And the favorable treatment of Cuban immigrants in the United States facilitated their material success in their new country. The 1980 U.S. census found that 803,226 Cubans lived in the United States. Their median family income was $18,245, not far below the national median of $19,917; in contrast, the median family income of Mexican Americans was $14,765; and of Puerto Ricans, $10,734. Their material success reinforced differences in values between the Cuban émigré community and the Cuban Revolution. As Arboleya has observed, the conflict of the Cuban emigrants with the Revolution during the period not only was related to an interest in recovering lost status, properties, and privileges, but also was rooted in values, in a form of life and individual goals at variance with the new norms of Cuban society.

By the 1970s, the evident failure of the Cuban counterrevolution to cause the fall of the Revolution led to a decline in its credibility and influence in U.S. society. The presidential administration of Jimmy Carter initiated steps toward the normalization of relations with Cuban under a rubric of peaceful coexistence, and at the same time, the Cuban government initiated dialogue with organizations and prominent persons of the Cuban-American community that favored peaceful coexistence with the Cuban Revolution.

However, the fortunes of the Cuban-American counterrevolution were revitalized with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Since that time, the Cuban-American Right has been able to strategically insert itself into a position of influence in the neoconservative sector of the U.S. political establishment.

At the same time, since 1980, the Cuban-American community has become more socially and ideologically diverse, fed by an economically-motivated Cuban emigration. In addition, significant changes have occurred in the world: a profound structural crisis of the world-system has been evident since the 1970s; and since the late 1990s, revolutionary Cuba has emerged as an important paradigmatic nation in the shaping of an alternative, necessary road for humanity.

Accordingly, it would be fair to say that neither the world-system nor the Cuban-American community are what they were in the early 1960s, while Cuba has persisted and has sustained itself on the foundation of the principles that it formulated at that time. These dynamics create transforming possibilities for the role of the Cuban-American community, which, as always, has to define who and what it is in relation to both Cuba and the United States.

In anticipation of the Fourth Conference on “The Nation and the Emigration,” which will take place in Havana from April 8 to April 10, we will continue to devote commentaries to themes related to the Cuban emigration.

Source

Arboleya, Jesús. 1997. La Contrarrevolución Cubana. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.