Economic crisis and emigration

Commentary by Charles McKelvey

March 11, 2020

In recent commentaries on the Cuban emigration, we have seen that the triumph of the Cuban Revolution on January 1, 1959 provoked emigration by personas whose economic and social privileges were adversely affected by the revolutionary measures, and who from Miami provided the social base for the U.S.-supported counterrevolution; and we have seen that there emerged in 1980 a different kind of emigration, consisting of persons whose desire to emigrate did not emerge from fundamental differences in class interests.

The economic crisis of the early 1990s in Cuba, resulting from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc, provoked another wave of emigration by those Cubans who were oriented to facing the challenge of migration in order to amplify their options in a more developed society. The majority were relatively young white males with a high cultural level, motivated by personal aspirations that could not be satisfied in Cuba, given the economic crisis of the country. A study by the Center for Studies of Alternative Policies of the University of Havana showed that the majority of the emigrants of the early 1990s did not consider the North American system as the ideal model of society; rather, they viewed Cuban society before the economic crisis as the ideal.

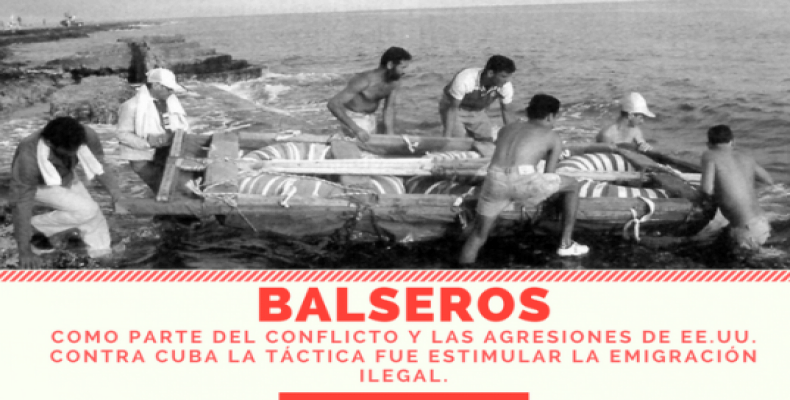

The great majority of the Cuban emigrants in the early 1990s entered the United States illegally. Between 1991 and July 1993, the United States received 12,808 illegal Cuban immigrants, while only 3,794 entered with legal documentation. Although U.S. authorities continued to be affected by the “Mariel syndrome,” that is, a fear of the massive entrance of Cuban immigrants, the U.S. government continued with its political game of stimulating Cuban illegal immigration through favorable reception upon arrival in U.S. territory, confident that Cuban restrictions and control would maintain the number of illegal emigrants at a level that would be economically and politically manageable for the United States. Indeed, between January 1990 and July 1994, Cuba impeded the illegal departure from the country of 37,801persons.

However, in the context of the economic crisis in Cuba, the migratory pressure was provoking a growing level of conflict between the Cuban government and would-be illegal immigrants. In the summer of 1994, the continuous hijacking of vessels with losses of human life in some cases as well as the breakout of altercations in Havana led the Cuban government to decide on August 12 to eliminate the restrictions on illegal departures. As a result, 36,000 persons launched homemade boats toward the United States, confident that they would be rescued at sea by the U.S. Coast Guard, as had occurred up to that time. The phenomenon adversely effected the reelection possibilities of U.S. President Bill Clinton and of Florida Governor Lawton Chiles. In response to the situation, the Clinton administration announced that it would impede the boatpeople from entering U.S. territory, thus breaking the exceptional migratory policy of stimulating illegal emigration, which the United States had maintained with respect to Cuba for thirty-five years. The administration announced that the boatpeople would be detained in U.S. military bases, and they would not receive the special benefits that had been applied to Cuban migrants, such as being granted the right to political asylum. In a few days, more than 30,000 Cuban emigrants were detained in U.S. military bases in Guantanamo and Panama.

Although the majority of the Cuban-American community rejected the new measures, an important part of U.S. public opinion favored a search for a resolution of the migratory problem and for the normalization of relations between the two countries. Accordingly, the Clinton Administration on September 9, 1994 signed the first migratory agreement between the United States and Cuba that sought specifically to control illegal migration. In the agreement, the U.S. government committed to conceding a minimum of 20,000 visas annually, while the Cuban government promised to control the illegal migratory flow from its coasts toward the United States. A second agreement signed on May 2, 1995 concerned the 30,000 boatpeople detained in virtual concentration camps in U.S. territory. The agreement allowed for: the gradual admission into the United States of those confined in Guantanamo; the return to Cuba, after that moment, of illegal migrants captured in the high seas; and the suspension of the practice of granting automatic asylum to those who manage to arrive by sea to U.S. territory. For its part, the Cuban government agreed to committed to receive those returned without taking judicial measures against them. Janet Reno, U.S. attorney general, declared that these measures represented a new step toward the regulation of migration from Cuba.

In order to not alienate the Cuban-American Right through the migratory accords, the Clinton administration accepted its demands for the prohibition of transfer of dollars to Cuba, the interruption of contacts between the Cuban-American community and the island, and an increase in the radio and television transmissions toward the island.

However, in spite of these significant concessions, the U.S. government response to migratory crisis of 1994 made it evident that the influence of the Cuban-American Right was not what it previously had been. The Cuban-American Right had been totally excluded from the process of negotiations concerning the migratory agreements, because its interests contradicted those of the U.S. administration as well as U.S. public opinion, and because of the administration’s awareness of the emergence of other voices in the Cuban-American community.

Under the migratory accords, the U.S. government granted 95,360 visas from 1995 to 1999, and 128,000 during the first decade of this century. Some 92.9% of the immigrants were white, significantly higher than their percentages in the Cuban population. And the level of education of the migrants was higher. Many of the migrants during this period gave high priority to the maintenance of relations with their families in Cuba.

The new characteristics of Cuban emigration since 1980 have led to an increase in the social and ideological diversity of the Cuban-American community. But this is not the only change since the early 1960s. At that time, there were few signs of the impending structural crisis of the world-system, which has become increasingly evident since the 1970s. And since that time, various factors were driving a U.S. relative economic decline, which the U.S. power elite has reinforced with shortsighted policies. Meanwhile, Cuba has persisted in its revolutionary road, not only consolidating its revolution, but also emerging as a paradigmatic nation, pointing the direction to a possible and necessary alternative road for humanity.

The evolving dynamics with respect to Cuba, the United States, the world-system, and the Cuban-American community create the possibility of a new role for the Cuban-American community; a new role beyond the apparent options of counterrevolution and peaceful coexistence. Could that new role be that of emissary of the Cuban Revolution in the nations of the North, educating the peoples of the North from the vantage point of the South?

In anticipation of the Fourth Conference on “The Nation and the Emigration,” which will take place in Havana from April 8 to April 10, we will continue to devote commentaries to themes related to the Cuban emigration.

Sources

Arboleya, Jesús. 1997. La Contrarrevolución Cubana. La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

__________. 2013. Cuba y los cubanoamericanos: El fenómeno migratorio cubano. La Habana: Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas.